Secret Operations: The Peruvian Charged with Laundering Massive Amounts of Drug Money

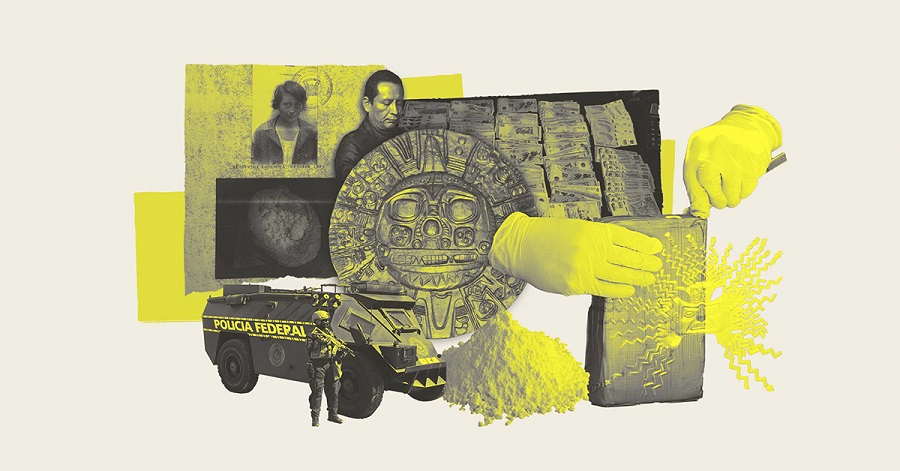

For decades, Carlos Sein Atachahua allegedly led a global money laundering empire. Police say his gang’s drugs, sent with logos depicting ancient Peruvian symbols, reached Italy’s ‘Ndrangheta and other criminal groups, while corrupted money-exchange houses around the world were allegedly used to launder profits.

By Miguel Gutiérrez (El Comercio), Iván Ruiz (Infobae), Guillermo Draper (Búsqueda), Cecilia Anesi (IrpiMedia), Milagros Salazar (Convoca), Gonzalo Torrico (Convoca), Daniela Castro (OCCRP), Nathan Jaccard (OCCRP) y Romina Colman (OCCRP)

July 6, 2022

Carlos Sein Atachahua Espinoza sometimes showed up to meetings dressed in stained mason’s overalls — not an outfit one might expect from someone charged with laundering money for a transnational drug trafficking organization. He looked more like a man who had been doing work around the house.

But behind this disheveled everyman appearance, the dark-haired Peruvian, 52, was a meticulously cautious — and very wealthy — man, according to Argentinian prosecutors. Those testifying against him say he dealt largely in cash and kept information compartmentalized among the people he led, keeping everything on a need-to-know basis.

He presented himself to prosecutors as a money changer or used-car salesman, and used aliases like “Abraham Levy.” At other times he carried credentials saying he was a fluid engineer with a degree from a Lima university.

For at least 14 years, authorities say, this approach worked. Staying under the radar, Atachahua laundered money for an Argentina-based drug trafficking empire from at least 2006 to 2020, with connections in Latin America, Europe, and North America according to testimony his accountant gave to Argentinian authorities.

Argentinian prosecutors have charged Atachahua with money laundering, and not drug trafficking. However, they have also alleged that he was involved in moving cocaine halfway around the world from its source in South America, often stamped with logos depicting Peruvian suns. Beyond Peru, he linked up with traffickers from neighboring Colombia as well as selling to Italy’s powerful ‘Ndrangheta criminal clan. As millions flowed in, it’s alleged he used corrupt money exchange houses on both sides of the Atlantic to launder profits made on the European market.

Atachahua was finally arrested on money laundering charges in Argentina in 2020, two years after his longtime accountant, Diego Xavier Guastini, turned against him and began providing information to authorities on his boss. By that time, Atachahua’s criminal file alleges, his group had used a fortune in dirty money to set up sham companies and buy up millions in Argentinian real estate, including parking lots. Reporters also found various properties and land parcels connected to Atachahua and his family in Peru.

Atachahua has served time in Peru on drug charges, while he and Guastani were both investigated by Uruguayan police for trafficking. Guastini alleged in interviews with Argentinian prosecutors that Atachahua ran a low-visibility global drug trafficking organization that worked with other networks to move cocaine to Europe.

While investigating Atachahua’s suspected money laundering activities, prosecutors found “unjustified economic increases,” which they said were “in line with alleged laundering maneuvers of assets derived from drug trafficking.” Argentinian prosecutors declined to comment on why Atachahua has not been charged with drug-related offenses or whether he might be, because “it’s an ongoing case.”

Carlos Sein Atachahua, left, is taken into custody in Buenos Aires. Credit: Gendarmería Nacional Argentina.

As he awaits his fate, monitored from his Argentina home via an electronic ankle bracelet, OCCRP and partners have unraveled Atachahua’s network –– and showed how he avoided detection for so long. His operations were revealed through court documents, interviews with authorities in South America and Europe, and immigration records, as well as property and company information.

The organization Atachahua was involved in is accused of laundering at least $7 million, but authorities told the press in 2020 that the figure could be much higher. Guastini told authorities that Atachahua took pains to conceal his illicit activities because he had ambitions of eventually going straight.

His plan was, over time, to become an above-board businessman, the accountant said. “What he wanted was to have a clean, legal, commercial umbrella, so that his children could see that he was going to work.”

If that ever happens, Guastini won’t see it. In October 2019, a few days after he gave a third debriefing to authorities about Atachahua, the accountant was shot dead.

Argentinian news outlets reported that a Toyota truck blocked the path of Guastini’s Audi A4 as he drove through a suburb of Buenos Aires. Then, a gunman on a motorcycle blasted him three times. “They hit me, they hit me,” he reportedly said to a bystander who helped him to the sidewalk. Guastini died from his wounds at a nearby hospital.

Atachahua has not been accused of the murder of his accountant, who had links to other, unrelated criminal groups. Allegations against Atachuaha from police and other sources, and in official indictments, have not been proven in court.

Through his legal team, Atachahua declined to comment.

Diego Xavier Guastini’s car is seen with bullet holes shot through its side, after he was killed while driving through a Buenos Aires suburb. Credit: Infobae (Argentina)

In 1999, he had his first recorded brush with the law, when he was arrested and later sentenced to nine years in prison in Peru for drug trafficking and document forgery, after cocaine was found in a car he was riding in. He was freed early for reasons that remain unclear, and by the mid-2000s had made his way to Argentina.

Settling in the upscale Caballito neighborhood in Buenos Aires, Guastini said Atachahua started off selling drugs locally. But he soon broadened his horizons, taking his cocaine — believed to have been sourced in Bolivia or Peru — to Europe, via exit points in Uruguay and Brazil.

Guastini explained to authorities how his boss networked with Colombians, Uruguayans, Chileans, and Italians — all with their own established trafficking routes — in an effort to “corporatize” his business and move it out of the slums.

Peruvian flight and border data obtained by OCCRP supports this account, showing that the ambitious Atachahua was already traveling to Brazil and Chile as early as December 2002.

Guastini alleged that once cocaine was sourced, it was moved overland across South America in private vehicles and commercial trucks carrying products such as bananas and toiletries. The packages, Guastini said, were stuffed into secret compartments in the chassis and locked in place with expanding foam.

The “merchandise” marketed by the organization Atachahua is alleged to be associated with was often marked with a Peruvian sun, evoking Incan tradition and his indigenous origins, Guastini said.

The organization avoided searches, even if it meant longer trips. Sometimes an operation could take 40 days, Guastini told authorities, with consignments sent in winding routes to Brazil and elsewhere before being shipped to Europe.

Guastini claimed that in 23 years of business, Atachahua’s organization “had not had a single loss.” Atachahua, he alleged, often followed shipments around the world, making appointments to meet buyers and liaise with underworld contacts. Immigration logs from Argentina and Peru show that he used at least eight passports or national IDs on his travels overland and by air.

Border records from Argentina show that from 2008 to 2020, Atachahua traveled in and out of the country over 200 times — nearly two-thirds of the time to Peru. He also traveled 18 times to and from Canada, where his daughter lived. Peruvian border records show him making 290 trips in and out of the country between 2002 and January 2020, including journeys to Panama and Chile.

According to Argentine authorities, after his daughter turned 18 in 2012, she began receiving fictitious donations from her parents. These donations, authorities believe, were designed to “remove a shadow” from their own assets, all of which had been acquired with the proceeds of crime. They also made donations to an upscale school in British Columbia.

However, for someone in the drug business, Atachahua’s leadership style and patient approach to business were unusually modest, experts say. He wasn’t interested in the golden handguns, celebrity meetings, or lavish haciendas often flaunted by narco-barons in Colombia and Mexico.

“Most drug traffickers have that weak point, that they always seek to display their profits, to show off, because that is the purpose of their business,” prosecutor Eduardo Castañeda, from Peru’s Specialized Prosecutor’s Office Against Organized Crime, told reporters.

By contrast, Castañeda said, Atachahua’s approach was “something particular.” It was an approach characterized by abundant caution.

“He always said that a person has to know 20 percent of the operation, that if they knew more than 20 percent, it was risky. Even his wife knew 20 percent of the operation,” Guastini told prosecutors.

Credit: Edin Pasovic/OCCRP

A Money Laundering Machine

Once the organization had offloaded its cocaine in Europe and elsewhere, Atachahua needed to get the profits back to South America, the indictment alleges. Sometimes, he sent cash into Peru and Argentina using “mules” who brought it in their hand luggage on commercial flights. Other times, he used currency exchange houses in Italy.

To do this, the accountant, Guastini, said he would personally pick up cash in Spain before driving it to northern Italy in a rental car. There, he said, he delivered money to Chavin Cash, an exchange house near Milano Centrale train station run by a Milan-based Peruvian named Hector Valdivia Chavez.

When Peruvians legitimately sent money from Milan back to their families, Guastini said, Valdivia would add extra cash to the amount. The Argentinian criminal file says Guastini would give Valdivia a contact in Lima who could withdraw the alleged narco-trafficking earnings. At other times, mules would carry cash to Peru, and take the illicit earnings to exchange houses in that country.

Guastini said Gomer River Cortez Galvez, owner of a Peru-based money exchange called Mister Dollar, took in the suspicious cash they brought. Reached by phone, he denied knowing Atachahua or Guastini. “All kinds of people come here with money to change, wanting to change dollars,” he said.

Valdivia did not respond to a request for comment.

Cash was often carried along the same overland routes allegedly used by the organization to smuggle drugs from Peru to other countries, according to Guastini’s testimony.

Money that made its way to Argentina was allegedly laundered using four companies set up by the organization, with front people — including, prosecutors believe, Atachahua’s wife Maribel del Aguila Fonseca, as well as his daughter. The funds were used for buying up garages and real estate.

Guastini said a good deal of cash was converted into gold coins bought from Argentina’s Banco Piano without invoicing, and then hidden in false pipes in the walls of an apartment inhabited by an elderly couple. Atachahua had brought them to live there in order to give this golden bunker the appearance of an ordinary home. But when Argentine authorities raided the place, no coins were found.

Elsewhere, the family appears to have funneled money into the gas industry.

In the region of San Martín in the Peruvian Amazon, the Atachahuas established a fuel-sales company called Inversiones NCN S.A.C., with branches in the northern provinces of Rioja, Moyobamba, and Mariscal Cáceres. The company’s general manager is Neddy Luz Atachahua Espinoza, Atachahua’s sister.

The station, flanked by cargo trucks, does not have any listed address and can only be found by asking locals for directions. Workers there told reporters that day-to-day operations were run by outside administrators and that Atachahua’s sister rarely visited.

Close Calls

The Atachahua money-moving business was not without its mishaps.

In 2007, two mules were nabbed at Barcelona airport carrying 400,000 in undeclared euros, according to Spanish authorities. Authorities seized the vast majority of the cash.

In June 2012, Atachuaha and Guastini went to Amsterdam via France to meet people Guastini described in his testimony to prosecutors as “the Calabrese” –– presumed to be the ‘Ndrangheta crime group from the southern Italian region of Calabria. Immigration records back up Guastini’s version of events.

A few months later, in November 2012, Uruguayan police launched an operation against Atachahua’s operatives based on an anonymous tip. The tipster told police about a house where suspected drug dealing was taking place. They put the house under surveillance and noticed a vehicle with Argentinian license plates. Police made arrests that hinted at the global links the group had made.

One of those detained was Francesco Pisano, an Italian working as a trafficker for the ‘Ndrangheta. Two Argentinians and two Uruguayans were also arrested, and more than 276 kilograms of cocaine were seized, along with over 47 kilograms of cocaine paste.

Atachahua and Guastini got away, but their meetings with those arrested had been captured on video. So was his departure: At 1:13 a.m. on November 24, 2012, just before the police swooped in, Atachahua’s Renault Megane was recorded crossing the Fray Bentos bridge linking the two countries.

According to Uruguayan authorities, Pisano had struck a deal with a Uruguayan trafficker which would have seen the drugs taken to Calabria from the port in the Uruguayan capital Montevideo.

Crucially for the Buenos Aires-based Atachahua, Uruguayan police did not share information about him and Guastini with their Argentinian colleagues. One Uruguayan police source close to the case said they “did not trust” Argentinian federal police at the time, because they had not been fully cooperative.

According to Guastini, Atachahua’s group had also succeeded in intimidating a witness away from appearing at a key hearing, further disrupting the investigation. After a change in prosecutors, Guastini said, the case against both him and Atachahua became “paralyzed” and was unsuccessful.

Atachahua would not be tracked down for years.

Atachahua’s Downfall

After this close call, Atachahua seemed ever more determined to squirrel his proceeds away. In 2013, his daughter was gifted shares in her parents’ companies — firms that are now the subject of the Argentinian investigation.

By 2016, she began a life in Canada, and two years later was engaged to a Canadian citizen. Guastini, meanwhile, was embarking on a partnership of his own: Starting in 2018, the accountant began providing information about Atachahua’s operations to Argentine authorities.

Over the following years, authorities slowly became better informed about Atachahua’s operations. The boss responded by making security adjustments.

According to Argentinian investigators, in the months before he was arrested in 2020, Atachahua was preparing to send a large shipment of drugs to Spain. He appeared to know he was being tailed, but managed to stay a step ahead. Every time he arrived in Argentina through Ministro Pistarini International Airport in Buenos Aires, he would circle the facility for at least an hour to lose the officers. “He always made it,” said one source close to the case.

Eventually, his luck ran out. In October 2020, he was arrested in a raid reported by media to have involved 400 Buenos Aires police officers who swooped in on 25 separate homes and businesses affiliated with the network. Authorities reportedly seized millions of dollars in cash in at least 10 different currencies, a gun, and 49 cell phones.

The next month, following the indictment of the organization’s main members, including Atachahua, a judge ordered the seizure of more than 30 billion Argentinian pesos, or roughly $383 million at the official exchange rate.

Peruvian authorities said they are not investigating Atachahua, and they have no information on Guastini or Valdivia, the money changer. None of the three men have been investigated in Spain or Italy either, according to authorities.

Just before Atachahua’s capture, his wife Maribel, who became a fugitive and subject to an international warrant after she traveled to Peru, left the country. In October 2021, however, she was arrested in Argentina, saying she had only left to visit her sick parents, and gave a statement to the authorities.

Atachahua’s daughter was also questioned when she traveled to Argentina in 2020, and banned from leaving the country again.

In a statement to a judge, Atachahua’s wife said it was the first time she had been “involved in a court case.”

She said she was “not [in] a gang or an illicit association.”

“We are a family.”

Antonio Baquero (OCCRP) contributed reporting.

Credit: James O’Brien/OCCRP

Menú

Menú

Buscar

Buscar

Sé el primero en leer nuestras publicaciones

Sé el primero en leer nuestras publicaciones