RSPO: Over a Hundred Complaints Fail to Curb Palm Oil’s Impact on Rainforests

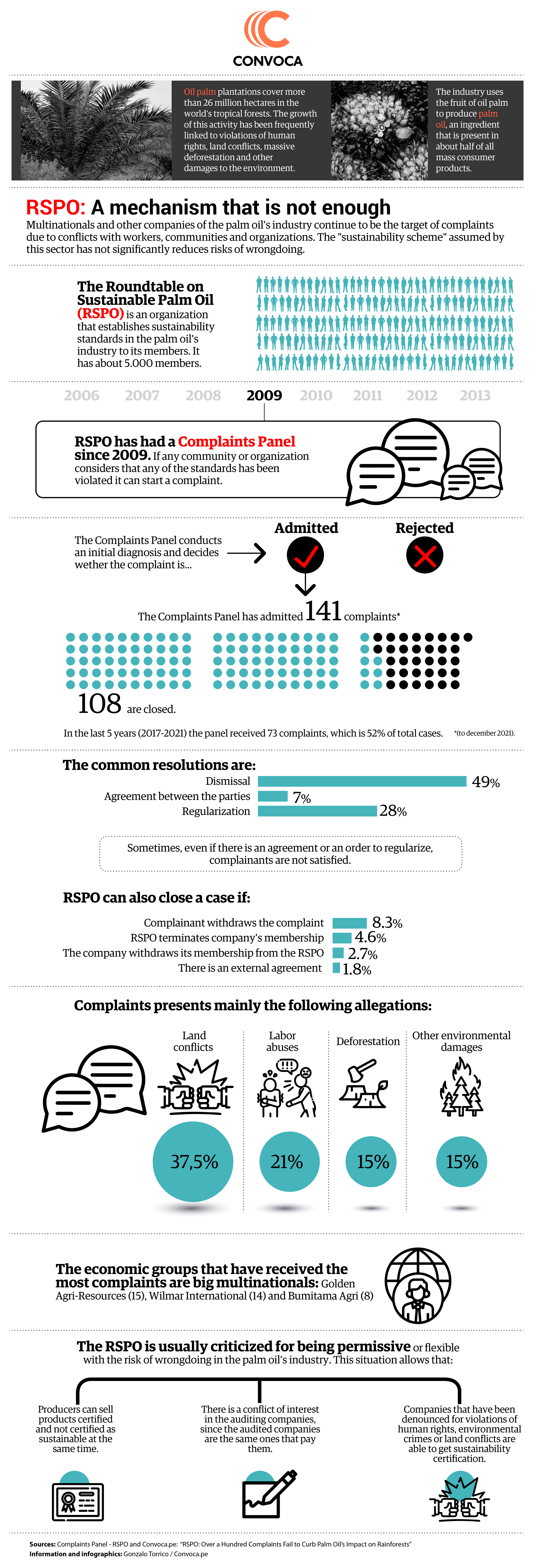

The RSPO, the renowned certification scheme of the international palm oil industry, has a Complaints Panel to report companies that do not meet its sustainability standards. However, after operating for 12 years, there has been a steady increase in new files. Disputes regarding plots of land, deforestation and labor abuses are the main objects of the complaints accumulated by the leading multinational companies. Convoca.pe analyzed the decisions by this “private court” that has processed 141 cases between 2009 and 2021. While many of these complaints, which were initiated by the affected communities and individuals, fall on deaf ears, others are concluded without resolving the underlying problems, as we revealed in this report from the “Tierra Herida” project, that Convoca.pe is publishing in partnership with the Pulitzer Center as part of the Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN).

By Gonzalo Torrico and Edwin Montesinos*

Edited by Milagros Salazar Herrera

Translated by Charlotte S. Beauclerck

June 9, 2022

Oil palm cultivation continues to decimate tropical forests in Asia, Africa and Latin America and no “sustainability certification” has managed to stop it. Since 1980, this economic activity has quadrupled its agricultural land in the “planet’s lungs.” In 2020, 26 million hectares were already being cultivated, a land area the size of Ecuador. The fruit of the plant is processed to produce palm oil, a raw material used in close to half of all the products on supermarket shelves and that we eat on a daily basis.

The rise of oil palm farming has been linked to predatory and illegal practices: deforestation, loss of ecosystems, labor abuses, conflicts with communities and environmental pollution. Even companies that have received a “sustainable” certification from the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), the leading international certification authority for the industry, are not free of questionable cases.

Convoca.pe, along with five grantee journalists from the Rainforest Investigations Network at the Pulitzer Center, reviewed the files processed by the Complaints Panel of the RSPO, a body created in 2009 to solve disputes between the affiliated companies and the communities regarding possible breaches of the sustainability policies. Between its creation and 2021, the global certification authority had processed 141 complaint files.

Of these, 108 are classified as “closed cases” and in 49% of them the process resulted in the dismissal of the complaint.

The issue reported most frequently by the complainants is territorial conflicts with palm oil companies. These represent 37.5% of the complaints admitted (53). The most common issues are the grabbing of the land or land disputes, which appears in 25 files, and the lack of consent or consultation of the owners, which appears in 22 cases. Another frequent problem is the breach of boundaries and invasions that are claimed in 13 complaints.

Palm oil production is also frequently linked to human rights violations and crimes against the environment, according to the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA). Indeed, other recurring problems reported to the RSPO’s Complaints Panel are labor abuses (21%) and accusations regarding deforestation (15%).

“Complaints procedures are certainly not the sole solution to non-compliance [with standards] and are definitely flawed but are still better than nothing which is why we continue to use them and work to improve them,” states Christopher Kidd, a policy adviser on territorial governance at the Forest Peoples Programme, an NGO that has accompanied several communities in different countries with their complaints.

Though the companies belonging to the RSPO represent only 19% of global palm oil supply, an analysis of the complaints sheds light on how the largest and most formal investments in the industry act, and on the effectiveness of the global certification authority.

Why are so many cases dismissed? “The Complaints Panel delivers a decision based on facts, the evidence before it and the findings of independent investigations where applicable. If there is insufficient evidence to support an allegation, then a Complaint may be dismissed,” the international certification scheme explains to Convoca.pe.

However, though as Kidd says, “it is better than nothing,” some of the complainants interviewed for this report feel that the RSPO does not do enough to dissuade and carry out the mission stated in its slogan, “transform the palm oil markets.” The complaints against the companies belonging to this certification authority have increased considerably over time. In only the last five years (2017-2021), 73 complaints were admitted by the authority: 51.8% of the entire record.

Palm fever in Asia

The oil palm has been installed in South-East Asia since the 19th century, when the colonial powers started to control access to the land and the supply of workers to develop the industry. In 1930, Asia managed to surpass production in Africa, the native continent of the plant. Since, Indonesia and Malaysia have become the world’s main production hub of this commodity, as they concentrate 85% of global exports. At what cost was this economic rise achieved?

A recent investigation published in the Journal of Land Use Science (Wagner and others, 2022) warned that 39.4% of the deforestation that occurred between 2000 and 2015 in the Malaysian Peninsula and on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia can be attributed exclusively to the expansion of oil palm.

Indonesia is by far the world’s largest palm oil producer. In 2021, it produced 45.5 million metric tons, 59% of the global volume. It holds a preponderant place in the Complaint Panel: 91 of the 141 files admitted for process concern this country. This is 64.5% of the total.

According to Global Forest Watch, deforestation destroyed 27.7 million hectares of Indonesia’s primary forests between 2000 and 2020. Greenpeace affirms that one in five hectares of oil palm planted there is illegal.

Indeed, in the world ranking of countries with the most complaints to the RSPO, the first places are occupied by very large economic groups with their main operations in the Indonesian archipelago. The company that is the object of the most complaints is Golden Agri-Resources, better known under the brand GAR, a multinational giant with its main headquarters in the tax haven of Singapore. Its subsidiaries have accumulated 15 complaints on the Panel: 13 for their plantations in Indonesia, one in Singapore and another in Liberia, Africa.

Golden Agri-Resources manages 536,000 hectares of agricultural land in Indonesia, distributed into 45 large plantations. It states on its website that it also owns 49 palm oil mills, and has another 378 third-party supplier mills. The accusations made most frequently against this economic group are related to territorial disputes (5), alleged labor abuses (4) and violations of RSPO policies (2). Moreover, one complaint has been recorded for a violent incident, in which shots were fired and six local farmers were injured.

Our team sent questions to the multinational company, but did not receive any answers to our requests. However, broadly speaking, the list of complaints against Golden Agri-Resources displays the frequent questioning behind the criticism of the industry’s supposedly “sustainable” label, and of RSPO itself.

For example, the first complaint received regarded the Roundtable being used to launder the reputation of its companies (“greenwashing”). According to Greenpeace, whose public denouncements pushed the RSPO to initiate the complaint, the multinational company signed up only two of the companies of its subsidiary group Sinar Mas as members (PT Smart and PT Ivo Mas Tunggal), which are involved in documented cases of mass deforestation, to “give the impression that it has achieved sustainability.” The issue was resolved rapidly when RSPO required that it include the entire group as its members.

The company with the second largest number of complaints is Wilmar International, the world’s largest palm oil refiner and commercialiser. It has 13 complaints, of which 11 are in Indonesia. The company has over 300 subsidiary companies. Its oil palm plantations alone cover a land area of 232,000 hectares, 65% of which are in the archipelago.

When asked for comment by Convoca.pe regarding the number of accusations received, Wilmar International responded that it is committed to providing the stakeholders with the “right platform” to raise their concerns and grievances. “It is with this spirit that we welcome our stakeholders to voice out, be it through the RSPO or our own Wilmar grievance procedure, instead of harassing or preventing them from doing so,” it stated.

This was not exactly the message sent to RSPO by the indigenous community of Luhak in Sumatra, which in 2018 accused a subsidiary of Wilmar International (PT Primatama Mulia Jaya Plantation) of using intimidation practices and criminalization against its population. The community was complaining that the company had installed an operations hub on its land without any consultation.

Indeed, the main issue resulting in complaints regarding Wilmar International to the Complaints Panel at RSPO is territorial conflicts. There is record of a total of nine complaints against Wilmar’s companies linked to that problem alone: seven in Indonesia, in the regions of Sumatra, Kotawaringin Timur and Kalimantan, and another two in Ghana and Nigeria, in Africa.

The other two complaints concern alleged environmental impact.

“For further clarification however, it is important to note that many of the cases raised against Wilmar were dismissed by the RSPO as they were either without merit or found to be unsubstantiated allegations. Additionally, the rest of the cases were successfully resolved through constructive engagement or mediation, resulting in the development and implementation of a agreed-upon resolution,” the company added. Of the 13 cases, 12 have already been closed and seven ended with the dismissal of the accusers’ allegations.

However, the closing of cases through “agreements” does not mean that the individuals who made the complaints are satisfied with the RSPO’s decision. For example, in 2013 Jakarta Animal Aid Network (JAAN) and other environmentalist organizations initiated a complaint against PT Mekar Mubi Andalas, a subsidiary of Wilmar, for not mitigating the environmental impact of its operations in East Borneo, not informing the stakeholders satisfactorily and not complying with the national regulations or the RSPO’s policies. The case was closed to be “monitored,” and the company was ordered to pay compensation.

“From our position the case remains unresolved until now, even though it was closed by RSPO. The compensation paid by the company (Wilmar) did not translate into any environmental improvement within or around the concession,” said Femke Den Haas, cofounder of JAAN. Wilmar compiled a High Conservation Values (HCV) forest assessment, which was however based on fallacious data. It was strongly criticized and rejected by all local environmental NGOs,” she added.

On this subject, Wilmar responded to Convoca.pe that these are “serious and misleading allegations.” The company indicated that its processes were reviewed by the RSPO and that the latter also suggested the compensation. The multinational company states that it was among the early adopters of the HCV methodology, an approach to assess all the important biological, ecological, social and cultural values for forests.

The third spot is held by another large company: Bumitama Agri Limited (Singapore), which in the past has had Wilmar International and Golden Agri as investors. It is the object of eight files at the Complaints Panel for alleged breaches, all in Indonesia. The cases of deforestation by the company have been documented by environmental organizations, for having affected the habitats of protected species such as the orangutan and gibbon.

One of the orangutans rescued from the logging carried out by Bumitama Gunajaya Agro, a subsidiary of Bumitama Agri Limited. Source: International Animal Rescue

In 2013, three of its companies received complaints for deforestation in High Conservation Value (HCV) forests. Its company PT Ladang Sawit had to stop its logging after orangutans were rescued from its land in early 2013. However, Greenpeace documented the fact that the deforestation continued, and affected an additional 1,500 hectares.

In recent years, the situation of orangutans in Indonesia has passed from being considered “endangered” to “critically endangered.” The Orangutan Foundation International estimates that every year between 1,000 and 5,000 of these apes disappear due to the expansion of oil palm.

Genting Group, based in Malaysia, and Musim Mas Holdings, domiciled in Singapore, are other industry giants that are next in the ranking, with six complaints each.

Export models

Access to land to cultivate monocultures is a significant issue in the tropics. As a matter of fact, academic research has already concluded that big investors have greater privileges to obtain large areas of land at lower prices than others. They are able to influence countries’ regulatory processes and have an uneven position of power to negotiate with the communities living on the territory.

In 2011, the Sungai and Dusun communities, in the north of the Island of Borneo, in Malaysia, saw the cemeteries of its villages demolished by heavy machinery and the trees on its mountains torn down with chainsaws. Since 2002, they have been involved in a legal dispute with the company Tanjung Bahagia Sdn Bhd, a subsidiary of the multinational giant Genting Group, which occupied their land.

“Despite our specific appeals to the company, the company has bulldozed our graveyards in all our villages. We have never seen a copy of the HCV assessment and HCV management plan,” the communities declared to the RSPO in the complaint submitted in 2011.

Genting Group is one of the multinationals with the most complaints against it: Fuente: Genting Finance Facebook

“We note that company plantings have been made right up the banks of important streams and small rivers. The company continued clearing our lands right up until 2011 without our agreement and without submitting information to the RSPO in line with the New Plantings Procedure (…),” they added.

On this issue, Genting Group stated that the RSPO closed the complaint in 2016 after the legal dispute was resolved through an agreement between both parties. “No ruling was necessary,” said Adli Rusli, assistant manager of Genting Plantations Berhad.

We also asked about the number of complaints that included accusations of deforestation, use of third parties’ land and causing risk to the environment. “[Genting] would like to put on record that the statements or allegations raised by you in the email are inaccurate and untrue, and we strongly disagree with these allegations,” he replied.

“We would like to reiterate that the planting activities undertaken by Genting were done in accordance to prevailing rules and regulations, including but not limited to, conducting a full environmental impact study to ensure High Conservation Areas are excluded (…),” Rusil added.

Though the territorial conflicts are concentrated in Indonesia (with 32 complaints, 70% of this type of complaints) and in Malaysia (with five of this type of complaint, 10%), these issues are reproduced in other regions. In Africa nine complaints were recorded (18% of this type of complaint), while in Latin America, three were recorded (6%).

Indeed, the mechanisms commonly used by this industry in South-East Asia, such as the requests for “land bank” - which involves asking the government to award state land to private capital -, have been replicated in recent years in the Amazon rainforest and have become a business for real estate speculation. The trafficking of land through fraudulent operations is another of the methods investigated by the authorities.

One clear example is the Melka Group, led by the American speculator Dennis Melka, which in 2007 managed to accumulate a 25,000-hectare concession in Sarawak, Malaysia for 99 years, from the State, through its company Asian Plantations (Singapore). After deforesting the area for the project and sowing it with oil palm, it sold the facilities to the large company Felda Ventures and achieved a threefold return on its investment.

American speculator Dennis Melka at Lima Stock Exchange. Photo: Gestión

It established a very similar, highly profitable scheme in Peru, at the expense of the country’s forests. In that country, the Melka Group managed to convince the Ucayali regional government to award 4,700 hectares of agricultural land to its company Plantaciones de Ucayali. Moreover, through another company, Plantaciones de Pucallpa, it bought 222 plots of land, a total of 6,800 hectares, from tenant farmers. This land is claimed by the indigenous community of Santa Clara de Uchunya as part of its ancestral land.

In response to the clearing of this land, the Organized Crime Prosecutor’s Office is currently investigating Melka and his collaborators for the alleged crime of deforestation.

The Shipibo community lodged a complaint at the RSPO regarding Plantaciones de Pucallpa, founded by Melka, which belonged to the global certification authority, for the deforestation of approximately 5,200 hectares that were mainly primary forest. The company had not taken any sustainability standards into consideration. In April 2016, the RSPO banned the company from continuing to deforest and plant palm until it resolved the complaint.

Peruvian Amazon forest cleaned by the palm oil industry. Photo: Convoca.

However, a month later Plantaciones de Pucallpa sold the plantations to a new company created by its own financers, Convoca.pe has revealed. Soon after, with no assets, the company withdrew from the RSPO, but not before it had left the plantations ready to be operated by a new company created by the same investors that financed the former’s activities: Ocho Sur. This new company has declared that one of its aims is to join the RSPO, while it denies being responsible for the deforestation carried out by Melka.

“The companies have constantly made a mockery of RSPO’s accountability measures. Whenever necessary, they have even left the certification body to evade any kind of responsibility without the international organism taking any measures to stop it. Therefore the [Complaints Panel] is a mechanism that, to say the least, has not worked as it should today,” says Álvaro Másquez, a lawyer for the indigenous community that has also submitted two additional complaints to the RSPO.

The native community is still currently involved in a legal dispute in the judiciary system to attempt to cancel the sales of the plots of land to Melka Group in 2012 by the individuals claiming to be tenant farmers, as the community considers them to be part of their heritage.

Pacific protest at the door of the Constitutional Court, where an audience was being held to assess the request for assistance by the Santa Clara de Uchunya Native Community. Source: Onamiap

In Brazil, the company Agropalma, certified by the RSPO since 2013, controls 39,000 hectares. In 2015, two Brazilian citizens lodged a complaint because the company acquired land that belonged to them and the State of Pará through fraudulent methods. The Roundtable dismissed the case. Nonetheless, in 2016 the Federal Police launched an investigation because Agropalma officials had falsified documents that were submitted to public bodies to “regularize” the ownership of land that they had occupied and was not their property

The Public Ministry for this village requested the cancellation of the fraudulent titles that covered an area of 9,500 hectares and, in October 2021, the Pará Court of Justice ordered the cancellation of the ownership. Recently, in March 2022, Agropalma was also condemned to pay around 188,000 dollars for “degrading work conditions” on its plantations. In both cases the company appealed and the case is still underway in the justice system.

Reputation recycling

Thanks to their climate, the tropics are an ideal location for large oil palm plantations. There, in warm and humid conditions, the production chain of palm oil starts, a product that has experienced a boom in recent years. Between 2007 and 2021, global demand for this commodity rose from 35 million to 72 million metric tons, according to figures from the United States Agriculture Department.

In this context, one of the main concerns of the companies in this growing industry is demonstrating that their products do not have a questionable, or even illegal, origin. However, monitoring the legality of the entire supply chain, from the cultivation of the plant to its final presentation in retail markets, is still a weakness of the industry due to the RSPO’s permissive policies.

For example, companies are still allowed to use a certification model on their supply chain called “mass balance.” The RSPO itself explains this with the following example: if during production 100 tons of palm oil certified as sustainable are mixed with 100 tons of uncertified oil, only 100 tons can carry a certified claim with the warning “mixed.”

Roundtable Nº 2 held in Switzerland, 2005. Source: RSPO.

In the process, different raw materials are combined, but in the result there will be a “balance” to calculate the certified production based on its volume, and not necessarily on its origin.

Moreover, the RSPO has also developed a system for manufacturers and retailers called “RSPO Credits.” A credit can be bought from a small farmer or refiner to certify a metric ton of their production as sustainable. In this way, a large buyer of credits can “compensate” - in the RSPO’s own words – for the volumes of uncertified palm oil used in their own processes.

“Trying to transform an industry is a process — RSPO Credits and Mass Balance (MB) supply chain models are important entry points for new members to become certified sustainable,” the RSPO explains to Convoca.pe.

“We encourage members to work towards the Segregated (SG) and Identity Preserved (IP) models, with time-bound plans,” the certification authority adds. The first of these “segregates” the certified production from the uncertified production, which can lead to companies using double standards. The Identity Preserved model is the only one that ensures that the entire production chain of the oil comes from certified sources.

“In order to continue providing economic incentives to growers, we need the flexibility of the Mass Balance supply chain to provide growers increased access to international markets,” adds the RSPO.

Oil palm fruit is processed in mills to produce palm oil. Photo: Mongabay.

An investigation by Greenpeace determined that between 2015 and 2017 alone palm oil suppliers for the multinational company Mondelez, a certified company that manufactures the famous Oreo cookies and Ritz crackers, deforested 70,000 hectares. Of these, 25,000 hectares were the natural habitat of orangutans, which are critically endangered.

The RSPO awards certifications for each category of the production chain. To do so, it has 26 certification bodies that assess, audit and certify compliance with the sustainability standards. Since its creation, the RSPO has been the target of criticism, as the entire process has allowed companies questioned for bad environmental practices to use their assessments and certifications to launder their image (greenwashing).

The EIA, in its report Who Watches the Watchmen? 2 from 2019, documented several cases of this mechanism of reputation laundering. Three years after its publication, Siobhan Pearce, an expert on Forests and Palm Oil at EIA, told Convoca.pe that it still has this perception, as she indicates that the RSPO has continued to certify companies that have committed clear breaches of its standards.

EIA has documented how the RSPO scheme is very permissive with the palm oil industry. Photo: EIA.

Pearce mentions the example of the companies Permata Putera Mandrini and Putera Manunggal Perkasa, subsidiaries of ANJ Group, which after deforesting primary forests in West Papua in Indonesia, obtained the RSPO’s sustainability certificate in December 2021.

“They cleared primary forest, which has not been allowed under the RSPO since November 2005, but yet no mention of this is made in the audit report and now are certified. The audit report only refers to [a document of the] New Plantations Procedures submitted in 2014 which were sub-standard and failed to identify the primary forest,” Pearce tells Convoca.pe.

The document from Procedures for New Plantations is designed to establish a series of assessments - created by certification bodies - that the companies have to pass before they can develop a palm cultivation project.

As evidence that the RSPO does not address the majority of incidents and problems that emerge in the industry - as the complaints are only initiated by reports - only one complaint has been recorded against ANJ Group since 2012 in the Complaints Panel, for alleged illegal logging and damage to orangutans by catching them with traps in East Kalimantan, in Indonesia. The complaint was dismissed due to “lack of evidence from the complainant.”

However “reputation laundering” does not only occur in South-East Asia, but also in Africa and South America.

For example, Pearce refers to the multinational company Socfin, whose operations in Sierra Leone, Africa, have been documented for violations of human rights, various conflicts with land owners and pollution. Despite this history, it obtained the RSPO certification in January 2022. The Dutch NGO Milieudefensie has warned that in the consultation procedures with the stakeholders carried out by the RSPO, the comments by some of them, such as the owners of the land, were not requested.

Oil palm plantation in Sierra Leone. Photo: Greenpeace.

Only one complaint has been recorded at RSPO regarding Socfin, from 2019, for occupying communal land, but in Indonesia, not Sierra Leone. The case was closed because the community withdrew its complaint.

In Colombia, the Italian company Poligrow, which operates over 7,000 hectares in the municipality of Mapiripán in the Amazon rainforest, obtained the sustainability certification in December 2020 without presenting the Procedures for New Plantations document, according to Pearce. The company has previously been involved in several controversies, due to reports for alleged labor abuses and because its director was prosecuted in 2017 for the crimes of aggravated fraud and criminal conspiracy, events linked to the acquisition of a plot of land. Its director was absolved.

Poligrow, like the previous cases, only has one complaint recorded at the RSPO, for taking control of land in the indigenous community of Mapiripán without its consent in 2015. The company agreed to rectify its actions, and the case was concluded.

Conflicts of interest

“The biggest weakness of the schemes is the lack of real independence of the auditors and Certification Bodies who have a conflict of interest as they are paid by the companies that they [in turn] assess. These weaknesses are noted by the Complains Panel and of course by the NGOs and complainants,” states Christopher Kidd, from the Forest Peoples Programme.

Each company belonging to the RSPO can choose their own certification body, therefore the latter compete among themselves to gain clients.

“The reluctance of the schemes to revise the way they carry out audits is the most frustrating aspect of our engagement with them [RSPO],” he adds. To date, the RSPO‘s certification bodies have certified the “sustainability” of 112 palm producing and milling companies belonging to the RSPO, which carry out the production stages that are most prone to breaches.

RSPO did not provide a direct reply regarding this question. “RSPO is also always working to improve its systems and processes to further strengthen the credibility of its standards. This includes regular training of Certification Bodies and auditors to further strengthen and ensure more comprehensive results in the audits conducted,” it replied to Convoca.pe.

Next, it refers to the fact that it reviews its standards every five years, to be aligned with the criteria of the ISEAL - a partnership that includes other institutions similar to the RSPO, but in different industries, such as soy, cotton, etc. - to demonstrate that the palm oil certified by the RSPO “is trustworthy and inclusive.” It does not mention the conflicts of interest.

Siobhan Pearce, from EIA, mentions a series of measures that could be carried out to achieve true independence in the certifications, which should not be difficult to implement. For example, there should be a central organism that assigns the certification bodies to each company, instead of the company choosing its assessor. Another solution would be to qualify the competency of each audit to assign them, based on their ranking, to each company depending on their level of risk.

Mutu International headquarters Source: Mutu International

Currently, the certification body that has certified the most companies receiving complaints in the Complaints Panel is Mutu International, a international company focusing on clients in Indonesia and Pacific Asia. It appears at least 45 times on the records. We sent questions to the auditing company through different channels, but have not yet received a response.

One of the questioned international certification bodies is SCS Global, which is responsible for certifying the companies in the aforementioned multinational group Socfin. It operates in ten countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The manner in which SCS Global managed to certify Socfin in Nigeria, Cameroon, Sierra Leone and the Ivory Coast has been reported on by Milieudefensie. The NGO has concluded that the territorial conflicts and human rights violations were not taken into consideration in its certification process. The organization has consequently taken a series of measures.

According to the information collected by InfoCongo, the RSPO requested that ASI Assurance (a supervisor of the certification bodies) launch an investigation into the actions of SCS Global, in response to the reports by Milieudefensie.

On this subject, SCS Global limited itself to sending us a document from ASI with the progress of the complaint published on March 3, 2022. ASI concluded that the notifications for the consultation process were only issued in English, which violates the RSPO’s requirements.

Unsatisfied

Among the claims that have reached the RSPO’s Complaint Panel, for some the solution was reached too late, others were not even admitted to create a file and others, despite the evidence, did not advance or were closed.

For example, the Latin American giant Alicorp, a mass consumer goods manufacturer with its main headquarters in Peru, was the object of a complaint after a report by Convoca.pe revealed that it was supplied with palm oil from land deforested by the Melka Group in the Peruvian Amazon. The complaint, lodged by the Uchunya indigenous community from Ucayali, was not even admitted to be processed by the RSPO.

“The Secretariat conducted an initial diagnosis (…) and finds that the allegations of fact made in the Complaint against Alicorp, even if proven to be true, would not constitute a breach of any of the provisions of RSPO Key Documents,” the Roundtable responded to our question. It added that Alicorp used the aforementioned “mass balance” method (using fruits of mixed origin) for its supply chain.

Alicorp is one of the biggest mas consumer goods companies in Latin America. Source: Andina

“A highly dangerous fact was stated: that the RSPO makes it possible to mix palm from uncertified origin - an elegant way of saying ‘illegal’ - with palm of certified origin, provided that the companies maintain a register and do not exceed an annual percentage. By saying that these companies are not expected to ensure a 100% unadulterated flow of clean palm, they are clearing them of responsibility. We are deeply disappointed by this decision,” said Álvaro Másquez, the legal advisor of the community.

The RSPO indicated that in 2021, of the 12 complaints received, one was not accepted after an initial diagnosis.

However, though some organizations gave already openly expressed their concern, Transformations for Justice (TuK Indonesia) took the discontent of the communities of Kerunang and Entapang, in Indonesia, to another level: they lodged a complaint against the RSPO for not having resolved a pending complaint promptly enough.

In 2018, they submitted a complaint against the RSPO before the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) because the years were passing and they had not yet resolved their land-related issue with the multinational company Sime Darby. The dispute took place at the National Point of Contact of the OECD in Switzerland, where the RSPO was founded in 2004. TuK claimed that the RSPO was not complying with the OECD’s guidelines for the companies of its member countries, by not addressing their claim correctly.

OECD received the claims of East Kalimantan communities as they didn’t get responses from RSPO. Fuente: OECD Watch

In 2007, Sime Darby bought a plantation in East Kalimantan and did not respect the agreements that its predecessor had made with the communities to allow them to grow crops within the concession. With the OECD’s mediation, the parties agreed on the procedures to follow in order for the complaint to move forward, and signed a document on this subject in 2019. However, the complaint is still pending resolution.

Sime Darby’s plantation in the tropical forest.

Edi Sutrisno, executive director of TuK Indonesia, says that he is satisfied with the OECD’s decision. “Before the TuK Indonesia OECD complaint with Swiss NCP, the RSPO complaint system was ineffective and the system failed to deliver an agreed time-bound action plan among parties in disputes or complaints – many legitimate complaints dragged for years without proper remedies and solutions,” he declares.

“Now Dayak Hibun communities (key party to RSPO complaint and OECD complaint) are waiting for proper land restitution as RSPO standard required members’ compliance with Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) and human rights for affected indigenous peoples and landowners,” he added.

Nevertheless, the advance of mass deforestation and the grabbing of land for oil palm production across the world has not ceased. The Complaints Panel of the renowned certification body of this industry remains a weak court to dissuade companies from carrying out these bad practices.

*With the collaboration of Pulitzer Center Rainforest Investigation Network (RIN) fellows: Madeleine Ngeunga (InfoCongo), Karol Ilagan (Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism), César Molinares (360-grados.co), Yao Hua Law (Macaranga) and Bagja Hadat (Tempo). Maria Alejandra Gonzales (Convoca) and Keng Kuek Ser Kuang, data editor from RIN, also collaborated with this story.

Illustration: Manuel Gómez Burns

Menú

Menú

Buscar

Buscar

Sé el primero en leer nuestras publicaciones

Sé el primero en leer nuestras publicaciones