Convoca.pe reviewed over a hundred resolutions by the Tax Court at the Ministry of Economy and Finances, which examines the complex financial operations monitored by the tax collection agency SUNAT, as well as internal emails by the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca. This research confirm that lawyers helped businesses reduce their tax rate in Peru, by manipulating the transfer pricing of goods and services between associate companies.

In the documents from the Tax Court we identified cases of price fixing related minerals and services, which distributed benefits artificially between the mining companies within the business group. This scheme lowered the amount of tax authorities could collect in Peru. At least four of the cases investigated by SUNAT reveal suspicious transactions amounting to over 15 million soles (US$ 4.5 million). If the Peruvian government collects less tax, the communities from where the mineral is extracted receive less revenue (mining canon) to invest in their development.

In 2018 a team of 15 experts from the Department of International Taxation and Transfer Pricing at SUNAT in Lima, uncovered that important mining companies with foreign capital modified the prices of financial transactions between associate companies to limit their tax exposure. These companies dodged a total of 600 million soles in tax (approximately US$ 180 million).

In order to identify concrete cases, Convoca.pe reviewed over a hundred resolutions issued by the Tax Court at the Ministry of Economy and Finances, which resolves taxation disputes. We thus detected that five mining companies used these mechanisms between companies within the same business group to reduce their tax payments. In at least four cases suspicious operations worth over 15 million soles (US$ 4.5 million).

These companies are Southern Peru Copper Corporation, subsidiary of Southern Copper Corporation based in Phoenix, Arizona, United States, and owned by Grupo Mexico; Cerro Verde mining company, the largest copper exporter, operating in the district of Uchumayo, Arequipa province; Los Quenales mining company, a subsidiary of the giant Glencore Finance and which operates the Iscaycruz and Yauliyacu mines in the Lima mountain range; the Doe Run mining company whose production center is in La Oroya, Junin province, now under the control of a creditor committee; and Antamina, another large copper exporter belonging to Glencore, with its main operations center in San Marcos, Ancash, Peru.

District of San Marcos, Ancash, where the Antamina ravine is located. At present, it has more than 17 thousand inhabitants.

Photo: Municipality of San Marcos.

The infringements exposed by SUNAT on Southern Peru Copper Corporation and Cerro Verde were ratified by the Tax Court, while in the other three cases the court ruled in favor of the companies.This despite the evidence presented by the tax collection body, including the case of Doe Run.

These financial mechanisms detected by SUNAT, and which appear in the tax resolutions analyzed by Convoca.pe, have been standard practice in the last 15 years between companies of a same group, or between Peruvian firms with companies in countries with low or no taxation.

Children playing next to the Doe Run Peru operations center in La Oroya. Photo: Revista Ideele

In line with tax confidentiality regulations, the names of the companies at the center of these controversies in the Tax Court are crossed out in the resolutions in order to avoid identification, however Convoca.pe managed to discover them and cross the information with various sources and experts.

Besides the names of these companies, we identified services reportedly provided from abroad that were recorded as expenditures to pay less tax, the appearance of external factors such as humidity or “shrinkage” (reduction of the mineral during transportation) to modify the final sales price, the use of commissions for transactions abroad between associate companies, and loans taken by the Peruvian company as requested by the headquarters, with commissions and interests that lighten the tax burden in Peru.

Explore this map, by mining companies, and discover the connections between the main companies in each country.

In the next few months the Tax Court will debate the new cases presented regarding Transfer Pricing. Photo: El Comercio.

The transactions of these companies monitored by SUNAT are described in the resolutions of the Tax Court between 2019 and 2017, but cover events that occurred between 2002 and 2005. Disciplinary procedures for tax offenses can take up to ten years to be resolved in that court, under tax confidentiality rules.

One of these companies is Southern Peru Copper Corporation, which has operated in southern Peru since the 1990s. In September 2009, analysts from the National Office of National Taxpayers at SUNAT (PRICO) determined that the mining company had carried out suspicious commercial payments between 2003 and 2005. One of these was declaration payment emitted in 2003 for consultancy and technical advice provided by a company associated to the business group Southern, based in Mexico: SAASA, or Servicios de Apoyo Administrativos S.A.

The chairman of SAASA is Germán Larrea Mota Velasco, the mining magnate and current executive director of Grupo México, the largest mining company in Mexico and the third largest global copper producer. Grupo México is also the owner of Southern Copper Corporation and it subsidarary Southern Peru Cooper Corporation.

According to a contract signed in November 2000 between Larrea Mota and Óscar Gonzales Rocha, the chairman of Southern Peru Cooper Corporation, the Mexican company SAASA would charge Souther Peru Copper Corporation a total of US$ 7 million for financing costs, as well as for legal and corporate advisory services.

Conflicts over the Tía María mining project in Southern Peru got intensified in 2015. Photo: Alberto Ñique

The SUNAT auditors established that Southern Peru Copper Corporation had handed over generic documentation that did not credibly justify the real value of these services

The observation on the services provided by SAASA was taken to the Tax Court at the Ministry of Economy and Finances by Southern Peru Cooper Corporations.

The company presented a ‘Transfer Prices Study’ produced by the international auditing company Ernst & Young, which stated that these “payments for services carried out by SAASA complied with the “arm’s length principle”, that is, the amount charged by one related party to the other is the same as it would be in a competitive market. After a year of legal disputes, Tax Court confirmed that Southern Peru Copper violated the law with a resolution from July 21, 2010.

In 2007, two years before SUNAT uncovered Southern Peru Copper Corporation's tax scheme, officials from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) of the United States also challenged the value of the services provided by the company associated to the head office, Southern Copper Corporation. The IRS also sought to disallow part of the fees paid. The company recognized this before the United States' Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Camp of the Los Quenuales mining company, in the Sierra de Lima. Photo: Inversiones República S.A.

A colossal hole in tax revenue

By adjusting the transaction prices in accordance with their corporate interests, for years several companies avoided paying taxes in line with the real income of the business group, which for Peru represents a colossal hole in tax revenue of approximately 55 billion soles (US$ 16.5 billion). This amounted to almost half of Peru’s entire budget for 2014.

On 6 th December 2017, Víctor Shiguiyama, then-director of SUNAT, testified in front of Peruvian Congress' Commission of Economy, Banking, Finances and Financial Intelligence about the drop in tax income: 90 billion soles (US$ 27 billion), the lowest in a decade.

Shiguiyama suggested that the decline in tax revenue of 55 billion soles (US$ 17 billion) owed, in part, to tax evasion by manipulating the prices in operations carried out between companies within the same business group.

Globally, up to US$ 240 billion a year - between four and ten percent of the tax collected globally - is untaxed money that companies withdraw from the country in which they operate, to tax havens such as Ireland, Luxemburg or Bermuda, where these profits are not subject to any taxation, according to an analysis published in late 2015 by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Victor Shiguiyama, head of Sunat in 2017, anticipated what is coming in control of Transfer Pricing. Photo: El Comercio

In Peru, Tania Quispe, the former director of SUNAT, recognized in March 2014 that the operations declared for transfer pricing between 2007 and 2012 amounted to US$ 370 billion, of which 65% were international. It was identified that 590 companies carried out these transactions, most of which are “principal taxpayers” (PRICOS), she declared in a forum on taxation.

Quispe stated that there were “6,000 cases of mining concentrate exporters” making loans to countries with a low taxation rate.

Though transfer pricing has been considered to calculate income tax payments in Peru since 1996, the concept was implemented in 2001. Years later, broader regulation was included in 2006, but due to operational issues it was only concretized in 2017 when the Peruvian government accepted the inclusion of regulation suggested by the OECD.

These rules stipulate that since October of that year over 3,500 companies are obliged to submit a Local Report to SUNAT, that is, provide details on their operations with associate companies across Peru. 350 companies with more than 84 million soles as income should also declare the so-called Master Report, which details their operations with associate companies domiciled outside the country.

In this group of companies, approximately 20 companies whose head office is outside Peru or in a tax haven, and whose consolidated financial statement for the group is over 2.7 billion soles (US$ 800 million) must present a “country by country report.” The statements on operations are derived from the tax information that it communicates punctually with the tax authorities of the countries in which the head office is based and which audits the subsidiary.

The district of Uchumayo has more than 14 thousand inhabitants. Its name has a quechua origin and means "river of chili" or "small river". Photo: Rojinegro81

Fictitious commissions

The resolutions of the Tax Court analyzed by Convoca.pe detected two more cases involving Cerro Verde, which uses US capital, and Antamina, whose main shareholders are the Australian company BHP Billiton and Glencore.

In 2002, Cerro Verde deducted US$ 156,025,000 from its income for "sales commissions” paid abroad to an associate company. SUNAT requested that the sales have precise documentation. The papers submitted by the executives of the mining company did not convince the three spokespersons at the Tax Court, who finally confirmed the suspicions of the SUNAT auditors, because the company could not verify the payment of the commission to the associate company.

The SUNAT auditors also identified a service hired by Cerro Verde from another company within the same business group, for a total of US$ 1,380,000, which was also deducted from the company’s income for 2002. Moreover, the highest administrative authority declared that Cerro Verde could not attest that the service was genuinely provided, and the Court confirmed SUNAT’s resolution against the large copper producer.

At the time of going to press, the Cerro Verde mining company had not responded to our request for information on their dispute with SUNAT in the Tax Court.

Fanciful values

In 2007, SUNAT inspectors, during one of their document inspections on the Antamina mining company in the San Marcos district of Ancash, uncovered that the minerals extracted in 2004 were sold months later to companies in the same group, such as Teck Cominco (Canada), Metals Limited and Rio Algom Limited.

SUNAT argued that the final sales price was not adjusted to the historical value at that time, and that Antamina should have included US$ 3,580,475, an amount that was not included in the calculation of the tax due that year.

The executives of the commercialization area of Antamina claimed that the price agreed to during the final payment was what should be taken into consideration. The company argued that the definitive value of the transaction is dependent on the final payment, in which other factors such as humidity play a role. Dissatisfied with the fine imposed by the tax office, the company’s lawyers and accountants took the case to the Tax Court.

In 2014, ten years after the operation had been monitored, the mining company explained that the transaction price that SUNAT objected to “was not only subject to the fluctuations of the market price, but also to adjustments to external factors such as dry weight and humidity.” In no part of the resolution did the courtroom take into consideration that the operations between two companies that SUNAT objected to followed the instructions of the head office.

In response to our request, Antamina mining company stated in an email that the process “aimed to identify an opportunity to acknowledge the taxed income - first an estimated income, then the adjustment for the differential in line with the final payment.” According to the company, the decision of the Tax Court resolved this dispute with SUNAT.

It specified that the matter was not related to the issue of transfer pricing because “these were only issued years after the case” that the resolution addressed.

The decisions and strategies to manipulate prices are adopted by the company that controls the subsidiaries, according to the documents reviewed and interviews with experts. This becomes evident when the financial directors or marketers of the mining companies are summoned to SUNAT to explain the observations.

“They appear to have no idea why these instruments were applied in their tax planning. They have no capacity for decision” said a senior official at the National Office for Principal Taxpayers, who asked to remain anonymous.

One of the resources employed by companies to plan their tax scheme is using “hybrid products”, which consist in incurring a debt in exchange for a future purchase of the mineral.

Since 2015, SUNAT has detected that mining companies in the exploration stage were receiving millions in soles in loans from the head office, on condition of selling the production of the following five or six years. The purchase took place with a “special discount”, as a result of which the final sale of the minerals was reduced by several million soles, thus decreasing the amount due in taxes.

Photo: EFE

More companies with suspicious transactions

Sources with close knowledge of SUNAT’s taxation activities informed Convoca.pe that 1,000 companies are targeted by SUNAT auditors. To detect these suspicious operations, the analysts at the Office for Taxation and Transfer Pricing focused on the companies displaying the following patterns: million-sol profits, transactions for the sale of minerals and goods between companies in the same business group or its head office, in addition to complex export mechanisms through companies domiciled in countries with low or no taxation: the traders’ tax havens.

In SUNAT’s crosshairs are traders including the multinational company Glencore, whose headquarters is in Switzerland, and the Louis Dreyfus and Trafigura groups, devoted to the processing and commercialization of goods worldwide, including minerals from Peruvian companies. These multinationals possess offshore structures and carry out operations in various tax jurisdictions outside Peru.

To investigate traders is very important because they negotiate the price adjustments at the moment of acquiring the mineral concentrate and at the time of selling it, ensuring that the difference nets them a substantial profit. Since the source of a trader’s income is negotiating the price adjustments for the costs of transporting and treating the minerals with the companies from which they purchase them, SUNAT analyzes their operations more carefully.

The Panama Papers Connection

In addition to traders, it is necessary to know the role that lawyers play in these financial schemes.

The numerous manners of dodging the auditing processes for transaction prices in Peru, and the role played by law firms and tax experts were demonstrated in the wake of the Panama Papers, the mass release of documents from the Panamanian firm Mossack Fonseca in April 2016. One of these cases was of lawyer Mauricio Muñoz-Nájar Bustamante, director of the law firm Muñoz-Nájar Bustamante y Asociados, who acted as an intermediary between Peruvian companies and the Panamanian firm.

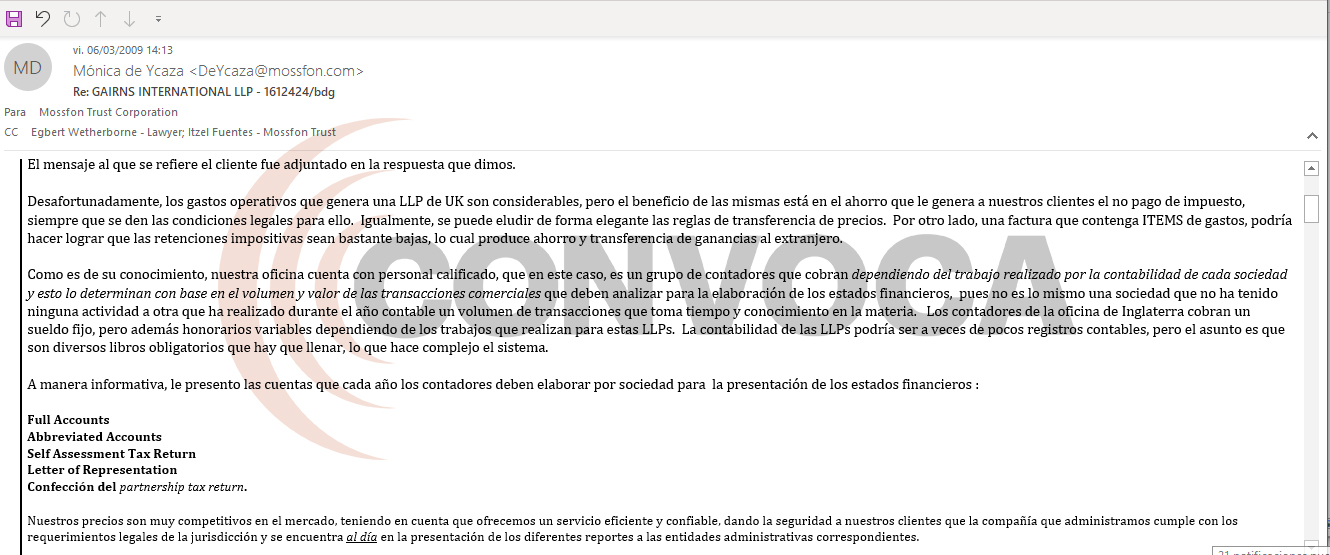

Convoca.pe identified part of the correspondence between Ramsés Owens, the director and main partner of Mossack Fonseca, and lawyer Muñoz-Nájar, in which they discuss how to “elegantly avoid Transfer Pricing” when planning operations between Peru and a company based in territories with a low tax rate.

“Unfortunately, the operating expenditure generated by a UK-based LLP (offshore company) is considerable, but the benefit of these is the savings from not paying tax for our clients, provided that the legal conditions are in place for this”, Owens wrote in an email from July 2009.

“Transfer pricing rules can be avoided just as elegantly", he continued, "on the other hand, an invoice containing items of expenditure could ensure a lower taxation rate, which results in savings and the transfer of profits abroad.”

Muñoz Najar finally opted for an offshore scheme in the United Kingdom to carry out his operations between Peru and abroad.

Ramses Owen, Mossfon lawyer who coordinated with peruvian lawyer Transfer Pricing. Today is required by american justice. Photo: CiudadPlus

Email of Mónica Ycaza to tributary lawyer Muñoz-Najar. Image: Panama Papers documents.

Insufficient control

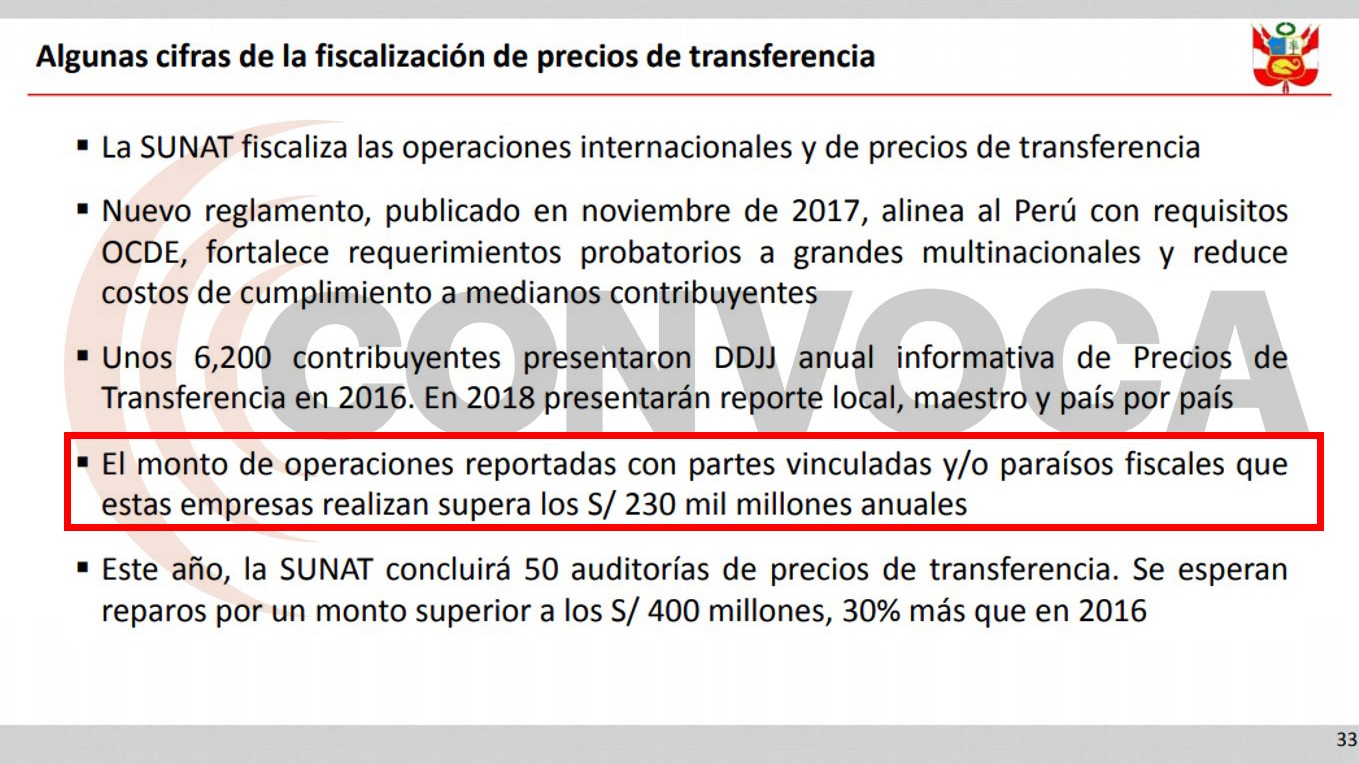

In 2018, around 2,600 transfer pricing declarations were submitted, from companies with national related parties in countries with a low or no tax rate. The operations reported for these transactions would be worth a total of over 250 billion soles (US$ 74 billion) a year.

In Peru, the 60 audits conducted by SUNAT identified transfer pricing manipulation to the tune of 400 million soles (US$ 117 million) in 2016.

“Very little has actually been done (to address the manipulation of transfer pricing); there are significant breaches”, said SUNAT officials consulted for this report.

To identify the sophisticated “price structures”, that allow companies to pay less taxes, SUNAT requires more trained staff.

Extract from the presentation made by the head of the Sunat, Víctor Shiguiyama. Image: Congress of the Republic of Peru

A study conducted by the International Tax Compact and the German Cooperation Agency (GTZ) in 2013 on the performance of the taxation agencies in Latin America determined that Peru lags behind other countries in the region and is far behind Argentina (with 130 controls), Mexico (87), Brazil (60) and Ecuador. In Peru SUNAT had only carried out 11 audits on export companies, six of which were devoted to mining.The report explained that mining companies' export operations cost US$ 27 billion per year.

Thanks to the new regulations in place since 2017 that strengthen Transfer Pricing auditing in Peru, SUNAT auditors are more consistently revelaing cacsed of price manipulation and how this affects lost tax revenue for country. The most egregious of these, based on the millions of dollars evading tax, will be examined in mid-2019 by the Tax Court.

This year, it is hoped that SUNAT’s Transfer Pricing teams will expand their auditing activities on all companies that display complex financial schemes, and notably large mining companies.

With the collaboration of journalists Anthony Quispe, Jackeline Cárdenas and Gonzalo Torrico.

Menú

Menú

Buscar

Buscar

Sé el primero en leer nuestras publicaciones

Sé el primero en leer nuestras publicaciones