Impunity and Death in Large-Scale Mining Camps

In the past fifteen years, more than 60% of the mining workers who died as a result of occupational accidents were workers who had been sub-contracted by large and medium-sized mining companies through outsourcing companies. The Buenaventura company of the Grupo Benavides, and Volcan, of the Swiss company Glencore, are responsible for the mining camps where the workers’ deaths are concentrated; these two businesses also lead the list of companies that most violate occupational safety standards. The outsourcing company with the highest number of registered deaths belongs to the business group of Brescia, one of the wealthiest families in Peru. The state entities in charge of mining safety and labor guarantees, the Supervisory Agency for Investment in Energy and Mining (Osinergmin) and National Superintendency of Labor Inspection (Sunafil), do not engage in joint work to guarantee safe conditions for the labor performed by these workers. The scenario is bleaker in the justice system: public prosecutors’ investigations into these deaths are shelved.

By Luis Enrique Pérez and Milagros Salazar Herrera | December 18th, 2020

While Martha Zuñiga Palomino and her seven-year-old son Luis slept in a small room in ice-cold Oyón, located some 3,145 meters above sea level, a rockslide in a mining camp about an hour away from their home suddenly and painfully changed their lives.

It was the early morning of January 26, 2008 in Oyón province, located in the highland area of the Lima region. Martha's husband, Eber Apaza Ricra, had been crushed to death between large blocks of stone at about 3:15 a.m. while working in the Uchucchacua shaft mine, which is owned by one of the most influential companies in Peru, the Buenaventura Company.

Apaza's thin 37-year-old body was handed over to his family fourteen hours after his death, recalls Martha. "They wouldn't let us go into the mine. We had to wait in one of the company's lounges; that’s as far as my son and I could go," she narrates, sobbing amidst the noise of the Oyón market, where she works selling fruit and vegetables.

The Uchucchacua mining camp is located at an altitude of more than 3,000 meters in the province of Oyón in the Sierra de Lima. Photo: Milagros Salazar / Convoca.pe

It has been more than twelve years since that early morning which enveloped Martha and her son Luis in a dense atmosphere of confusion and tears. The 7-year-old boy saw his father's 1.7-meter (5 foot 6 inch) body covered by a blanket in one of the facilities in Uchucchacua during the wait for the coffin. His brown-skinned face and his black hair were the only visible body parts. "I will never forget his face; it was purple. I was scared and crying, I said to my mom, 'Tell my dad to stand up. Let's get out of here. Why is he purple? Let's quickly get out of here," recalls Luis, who is now 20 years old. His father would have turned 50 this past September.

To this day, neither Martha nor Luis clearly know how Eber Apaza Ricra died in the darkness of that mine shaft on Saturday, January 26, 2008. That same year, another 63 workers died in occupational accidents in various mining camps in Peru. The Peruvian economy is sustained by the extraction of gold, silver, copper, zinc and various metals from the bowels of the Andes, which are then exported mainly to China, Japan, South Korea, India, Switzerland and the United States.

Testimony of Martha Zúñiga, widow of mining worker Eber Apaza Ricra

According to a database created and analyzed by Convoca.pe using information from the Peruvian Ministry of Energy and Mines (MEM), between 2006 and July 2020, 683 workers died while conducting activities for large and medium mining companies. Sixty-three percent of these workers, 432 of the total who died in this period, worked for a company that was outsourced from the mining company holding the concession; and they were performing high-risk tasks in mineral extraction and production.

The mining camp with the highest number of outsourced workers who died in occupational accidents during those fifteen years is none other than Uchucchacua. This camp in Oyón belongs to the Buenaventura mining company, whose director is Roque Benavides Ganoza, an Aprista Party member since September 2020.

Like many workers, Eber Apaza started work in the mine with a dream of a better future and a secure job. He and his wife Martha arrived in Oyón from Ayacucho department in 1997. He spent his last days working as a driller for the Contrata Minera Cristóbal E.I.R.L., which in turn provides services for Buenaventura in Uchucchacua. Buenaventura has a welcome sign that seems like an ironic response to the numbers of deaths in the mine shafts: "If it isn’t safe, it isn’t done".

Uchucchacua not only registers the highest number of deaths of outsourced mine workers, it also is the Buenaventura mining unit with the highest number of sanctions for non-compliance with occupational safety regulations between 2007 and May 2019, according to a database of the Supervisory Agency for Investment in Energy and Mining (Osinergmin) to which Convoca.pe had access.

"If it is not safe, it is not done", a phrase that stands out when entering Uchucchacua, the mining unit with the highest number of fatal accidents in the Buenaventura company. Photo: Milagros Salazar / Convoca.pe

The mining camps where hundreds of workers have died in occupational accidents are also in the hands of companies that, in several cases, for the past 14 years have ranked among those most sanctioned for failing to comply with safety standards.

Peruvian Ministry of Energy and Mines figures reveal that between 2009 and 2018, the large mining companies, with Peruvian and foreign capital alike, preferred to hire the majority of workers who carry out high-risk work, through outsourcing companies that in most cases offer lower salaries and fewer benefits, based on the documentation analyzed for this investigative report.

In 2012 and 2018, mining companies had the highest percentage of outsourced workers with 59% and 60% of workers, respectively. In the current pandemic era, the scenario has not changed. Between January and September 2020, more than 64% of workers in the extractive sector provide services through outsourcing companies.

The labor force to extract the metals from the strip or open pit mining is composed of workers outsourced by the large mining companies. Between 2010 and April 2019, the latter accumulated exports that surpassed 253 billion US dollars, according to the Ministry of Energy and Mines.

However, the oversight for the activities inside the mining camps has not advanced with the same pace as the profitability of the mining industry.

The Peruvian State has two institutions that monitor the sector amidst the gaps in the sanctioning process and scarce public transparency. Osinergmin is responsible for inspecting whether companies comply with safety measures in operations and the National Superintendency of Labor Inspection (Sunafil) oversees labor standards for workers. Yet the two entities do not work together to ensure the full compliance of the established regulations to protect the lives of workers.

The labor force to extract the metals from the tunnels or open pit falls on outsourced workers from large-scale mining. In times of pandemic, more than 64% of workers in the extractive sector provide services through contractor companies".

The Ministry of Energy and Mines’ General Directorate of Mining, which manages the official registry of outsourcing companies, assured Convoca.pe that it only maintains an official report on the number of deaths of workers in occupational accidents and that it does not have detailed reports of how accidents occurred or who is responsible. The directorate informed that this task falls under the responsibility of the supervisory institutions. Yet much of the information that would make it possible to identify companies’ level of responsibility has not been published.

While this occurs in the corridors of the institutions responsible for regulating and overseeing the mining sector, the state of investigations into these deaths is even more dismal in the justice system. Eight percent of the cases that were filed for the fatalities of outsourced workers who died in the Uchucchacua mining camp were shelved. Between 2008 and 2019, three were closed in the Mixed Provincial Prosecutor’s Office of Oyón and the remaining five were closed in the Judicial Branch. The case of Eber Apaza Ricra was one of these.

As this investigative report shows, the story of the deaths in the mining camps of the large mining companies transits between impunity, oblivion and resignation.

The Camps’ Powerful Owners

The deaths of the 432 outsourced workers primarily occurred in mining camps run by companies that have considerable influence in business associations and maintain ties to Peruvian politics.

Buenaventura is the company with the highest concentration of deaths due to occupational accidents of workers from outsourced companies. There have been 40 worker deaths in 12 of its production units between 2006 and July 2020. The highest number of fatal accidents at this company, owned by the Grupo Benavides, is at the Uchucchacua camp where 11 workers have died.

Roque Benavides (in the red circle), director of the Buenaventura mining company, is known for his Aprista militancy. His company contributed 200 thousand dollars for a campaign favorable to Keiko Fujimori. Photo: Diffusion

Buenaventura has received 138 sanctions for not complying with occupational safety regulations in 30 mining units between June 2007 and July 2020, according to the Osinergmin database. Thirty of these are registered in the Uchucchacua mining camp, the location with the most infractions.

The director of Buenaventura, Roque Benavides Ganoza, is an Aprista Party member and businessman who wields enormous political power. Currently, he is in charge of the team drafting the party platform for the Aprista Party's presidential candidate, Nidia Vilchez; the candidate was a minister in the government of former president Alan García.

The Buenaventura mining company actively participated in the second round of the 2011 general elections. It even contributed 200,000 US dollars to the country's main business association, the National Confederation of Private Entrepreneurial Institutions (CONFIEP), for an advertising campaign that supported the "social market economy" and the position of Keiko Fujimori's candidacy. Fujimori was running against then-candidate Ollanta Humala, who eventually won the presidency.

With 36 deaths, Volcan registers the second highest number of deaths of outsourced workers. This company also registers the highest number of deaths of directly hired and outsourced workers at the national level with 53 deaths between 2006 and January 2019.

Volcan, which since November 2017 is controlled by the Swiss transnational Glencore, registers the highest number of sanctions for non-compliance with occupational safety standards. This company has 161 sanctions in 14 mining units, according to the Osinergmin sanctions registry. The Volcan mining camps with the highest number of occupational safety violations also have the highest number of deaths of outsourced workers, which is the case in San Cristóbal and Andaychagua, located in the central highland department of Junín.

Andaychagua is one of the mines with the most fatal accidents among the Volcan mining camps. Photo: ProActiva

Over the past 15 years, Volcan has a history of repeated violations of labor and environmental regulations. According to the databases created and analyzed by the Deep Data platform team of Convoca.pe, Volcan is the top offender among the large mining companies.

The company's business is also linked to politics. Volcan donated money to the CONFIEP fund for the 2011 campaign. The company's vice president, José Ignacio de Romaña Letts, admitted as much in November 2019 to the Public Prosecutor’s Office’s Lava Jato Special Team, which investigates cases of corruption and money laundering that involves former presidents and presidential candidates who received under-the-table funding for their election campaigns.

Alpayana registers the third highest number of deaths of outsourced workers in occupational accidents with 23 cases in recent years. At several moments, its operations have triggered workers’ grievances. Yet the strike by outsourced workers in June 2007 when this company, owned by the Gubbins family, was called Casapalca, is the most well-known.

Upon entering the tunnels of the former Casapalca mine, it is stated that the first value of this company is "taking care of life". Photo: Luis Enrique Pérez / Convoca.pe

In that strike, some 1,700 outsourced workers claimed that they were being paid meager monthly wages, less than 400 Peruvian soles (about 110 US dollars at that time), as well as working in unhealthy and unsafe conditions. Two mine workers died in these protests.

Due to these grievances, which were documented by the Ministry of Labor in 2007, the National Society of Mining, Petroleum and Energy (SNMPE) expelled the Casapalca mining company from its business association. According to the transnational investigation on the Panama Papers, the owner of the mining company, Alejandro Henry Gubbins Granger, appears in the files of Mossack Fonseca, a Panamanian law firm accused of tax evasion and avoidance, as well as of covering up large fortunes of people and companies investigated for corruption, fraud and other crimes. Gubbins, along with his sons who have also held important positions at Alpayana, is named in the Panama Papers.

The company, which kept the name Casapalca until 2019 when it became Alpayana, has political ties to the Fujimori family. In September 2020, the La República newspaper reported that the Lava Jato Special Team the Public Prosecutor's Office knew that the company MVV Bienes Raíces, owned by Mark Vito Villanella, Keiko Fujimori’s husband, intervened in two real estate operations with this mining company that is managed by Alejandro Gubbins Cox.

In the 2011 presidential elections, Eduardo and Patricia Gubbins Granger, members of the family that owns Alpayana, contributed campaign funds to the Fujimori party.

Like the Uchucchacua camp that is in the hands of the Benavides family, in the Alpayana mining camp, owned by the Gubbins family, the camp has different signs that announce, "nothing is as important as security”. In the Casapalca mining center in Huarochirí (Lima department), located at more than 4,100 meters above sea level, other signs state "[the worker’s] life over production". Official records over the past 15 years indicate the contrary.

"If it's not safe, stop!" At the entrance to the Alpayana mining company in Huarochirí there are several safety messages for the workers. Photo: Luis Enrique Pérez / Convoca.pe

The Clan of Outsourcing Companies

The outsourcing companies with the highest number of worker fatalities in mining units are part of large economic groups. At the top of the list is Administración de Empresas S.A. (AESA), which between 2007 and 2012, registered 11 victims of mining accidents, primarily in the camps of the mining company Nexa Resources Atacocha S.A.A. and Compañía Minera Raura S.A.

AESA is the outsourcing company with the most safety violations, according to the Osinergmin registry. This company has six sanctions registered for operations in the camps of Nexa Resources Atacocha S.A.A. in Pasco and Compañía Minera Raura S.A. in Huánuco.

AESA belongs to Grupo Breca, owned by the Brescia Cafferata family; this is one of the most important economic conglomerates in Peru that also has investments in the mining companies of Minsur, Raura and Marcobre. In other words, the Brescia family, one of Peru’s wealthiest families, has commercial interests in the mining companies that hold the concessions and in an important company that outsources workers for high-risk operations.

AESA is part of the Breca Group, whose co-chairs are Alex Fort Brescia and Pedro Brescia Moreyra. Photo: América Retail

According to AESA's website, its workers currently participate in the operations of the Barbastro mining company in Huancavelica, Volcan in Junín and Minsur in Puno.

The AESA contracting company is followed by Servicios Mineros Gloria S.A.C. The latter company, founded in 2008, registers the death of nine workers and is currently in liquidation. Of these nine deaths, five were victims of occupational accidents in Volcan’s mining operations.

Servicios Mineros Gloria registers four sanctions for infractions of occupational safety and health regulations in its operations in Volcan camps in Junín and Pasco. According to the registry of the Ministry of Energy and Mines, these two locations are the sites of the deaths due to occupational accidents. Luis Alberto Wu Punchin is a founding partner and board member of the contracting company, which was founded in 2008.

Wu Punchin, who was general manager of America Television (Channel 4), is best remembered for having appeared in one of the 'vladivideos'. In this 1999 video, filmed in a lounge in the Peruvian National Intelligence Service (SIN) with Vladimiro Montesinos and the businessman José Francisco Crousillat, the three discuss a two million US dollar loan granted by the Military Police Fund to pay the debts of America Television. In 2017, Servicios Mineros Gloria S.A.C. entered into liquidation under the management of the liquidation company Dirección Integral y Gestión de Empresas S.A.C.

Incimmet S.A., which between 2006 and 2017 registered nine workers killed in mining accidents, ranks among the outsourcing companies with the highest number of victims. Seven of these cases were reported in three of Volcan’s mining units in the Junín region. Volcan has the second highest number of cases of outsourced worker deaths and leads the ranking of fatal accidents in mining camps in Peru.

According to data from the Ministry of Energy and Mines, Incimmet registered its last fatal accident in January 2017. The victim was 38-year-old Julio Santiago Travezaño who was a worker in the Milpo mining unit of Nexa Resources El Porvenir S.A. in Cerro de Pasco region, in the country’s central mountain range.

The union leaders for the outsourced workers insist that they are given the "hard work", which is that with the greatest exposure and risk. They usually do the rock removal, drilling, detonations, and other tasks that place their lives in danger if companies do not take the legally established safety measures.

"We participate in the whole mining exploitation process. We are operators, drillers, drivers, shovelers. We are in the danger zone; so why do they pay us less? Why don't we have the same benefits as the workers in the main company?" asks José Alcedo, assistant general secretary of the Union of Outsourced Workers of the Uchucchacua Mining Unit of the Buenaventura company, located in Oyón.

The leader of Uchucchacua, José Alcedo, assures that 80% of the workers of that mining unit work through outsourcing companies. Photo: Milagros Salazar / Convoca.pe

Alcedo asserted that 80% of the workers in this mining camp work for the outsourcing companies and only 20% are on the payroll of the mining company. Convoca.pe asked the Buenaventura company, through the consulting firm Apoyo Comunicaciones, to confirm the percentage of subcontracted workers in Uchucchacua. The company responded to other questions, but not this one.

Julián Morales, from the General Union of Workers that provide services to Alpayana S.A., asserted that the situation is similar in the former Casapalca mining company where 90% of the workers are outsourced and also are the primary victims of fatal accidents in the mines. Alpayana also avoided responding to the question.

The union of Alpayana S.A. affirms that 90% of workers are outsourced and are the main affected by fatal accidents in the mines".

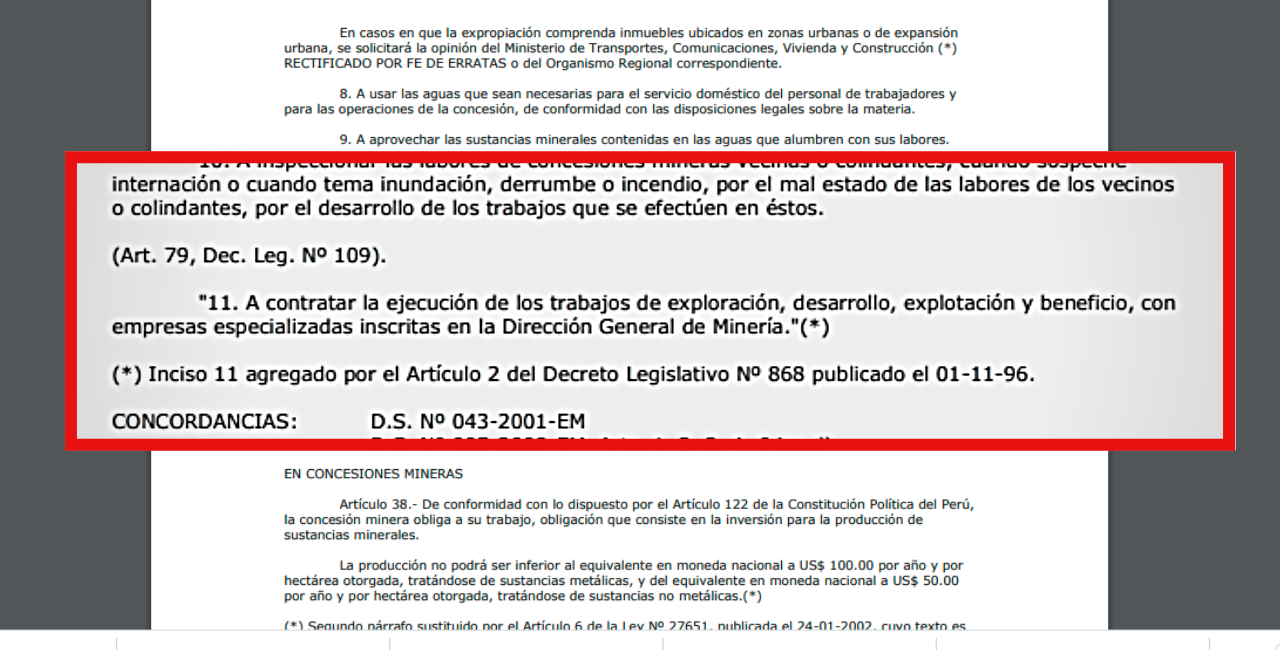

The history of outsourced workers dates back to 1996 during the Alberto Fujimori government. Fujimori promoted private investment along with a series of privileges for companies such as tax exemptions and flexible rules regarding labor and environmental rights. Since then, the General Mining Law has allowed mining companies that hold concessions to hire specialized companies to conduct significant work at all stages of production.

Twelve years later, in 2008 the State regulated the services of the outsourcing companies and established that they must directly supervise their workers and have their own technical and material resources, thus not having a dependence on the mining company that hires them. Labor lawyer Ynés Vergaray posits that there is no compliance with this obligation; in practice those who supervise the workers are the main companies or, as has been shown in the case of AESA that is part of Grupo Breca, the outsourcing company belongs to the same business family as the mining company.

In the government of Alberto Fujimori, mining incumbents were allowed to hire specialized companies for all large-scale mining processes.

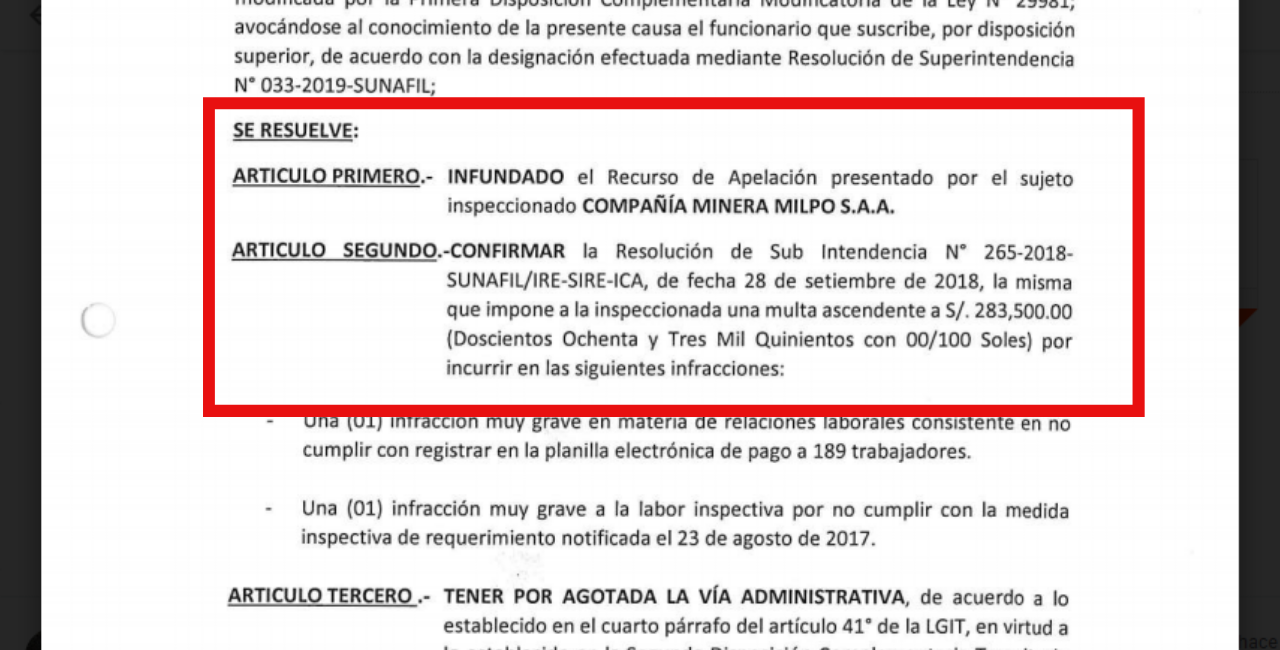

Despite workers’ grievances against the distortion of labor outsourcing, Sunafil’s public registry for the period from 2014 to 2020 only contains two sanctions for this against mining companies. Nexa Resources Peru (formerly Minera Milpo) is one of these companies; it was fined 283,500 Peruvian soles in 2018 (equivalent to slightly more than 85,400 US dollars).

Sunafil uncovered an extremely serious labor relations infraction. It confirmed that 189 workers of the Tecnomin Data S.R.L. and Eka Mining S.A.C. outsourcing companies maintained a direct relationship with Nexa. In addition to the fine, Sunafil ordered that these workers be put on the mining company’s payroll.

The Sunafil office in Huánuco also sanctioned Minera Raura, of Grupo Breca, when it found out that this company did not let the union know the identity of the outsourcing companies, the workers who were transported to the mine, and the activities conducted between May 2015 and December 2018. The January 2020 Sunafil resolution mentioned that this situation affected 419 workers.

The Milpo mining company, now called Nexa Resources Peru, was fined more than 283 thousand soles for denaturing the figure of labor outsourcing.

In the Alberto Fujimori government, the General Mining Law allowed specialized companies to be hired by the mining companies that hold the concessions".

Mine Collapses and Lack of Oxygen

Official records reveal that the most frequent fatal mining accidents are landslides or collapses inside the mines. In the past 15 years, these occupational accidents have led to the deaths of 145 outsourced workers. Another 52 workers died from asphyxiation or gas poisoning or radiation exposure. Other causes of death include traffic accidents during the transport of workers or materials and rock falls; a total 44 workers died in each of these classifications.

The outsourcing companies of IESA S.A. and Corporación Minera Geminis S.A.C. register the largest number of workers killed by rock falls in the mines; each register five victims each, according to the official registry of the Ministry of Energy and Mines.

IESA workers died while working for Volcan, Nexa Resources Atacocha, Nexa Resources Peru and Minera Ares.

In the case of Corporación Minera Geminis S.A.C., the five workers died in a landslide in the early morning of February 7, 2009, inside the Casapalca mining unit (now Alpayana S.A.) in Huarochirí province. One of the victims was Jhonston César Herrera Ccoicca, known as César, who was only 20 years old.

On that February morning, César Herrera received the order to enter the interior of the mine to do excavation work alongside four other workers. The young man had only been on the job for eight months; however, he accepted the order to accompany Eloy Chipana, Carlos Alberto Corpus, Edgar Villareal Bustillos and Alex Taipe Huamaní. All five were outsourced workers from Corporación Minera Géminis S.A.C.

While they were toiling in the mine shaft, at about 3:30 a.m. a block of rock suddenly fell off in an area near where they were working. This collapse also caused several platforms and rocks to collapse and fall, impacting the area where the five workers were located. The workers were trapped and died from asphyxiation and multiple injuries. The remains of César and his companions were only salvaged from inside the mine almost one week after the collapse.

Official records reveal that 145 contract workers died from collapses or burials and another 52 from suffocation or gas poisoning or exposure to radiation inside the mine".

Days later, Julio Herrera Quispe went to the morgue in Lima to identify the 1.60 meter-long (5 foot 2 inch) inert body of his son César. The last time the two had seen one another was in their family home, in Chanchamayo, Junín, to celebrate New Year’s Eve 2009, never imagining that it would actually be a farewell. César stayed with his parents until the first days of January and before returning to work at the mine he cried as he said goodbye to them and his older sister. "It was as if he had a feeling of what was going to happen," recalled his father, Julio Herrera.

César's story is echoed in several far-flung mining camps in Peru and amidst the silence and resignation of the relatives who lost their sons, fathers and husbands. Dozens of workers have died crushed by rocks and others from the lack of oxygen in the darkness of a mine shaft.

Servicios Mineros La Esmeralda S.A.C., Operaciones Mineras San Sebastian EIRL and Administración de Empresas S.A.C. (AESA) are the outsourcing companies registering the highest number of workers who have died from gas poisoning or asphyxiation in the mines. Each of the companies is registered with three workers’ deaths each, nine in total.

The three workers of Servicios Mineros La Esmeralda died from asphyxiation inside the mine of Compañía Minera Valor located in the Huancavelica region. Two of the workers, Efrain Jayo Cuellas and Mulato Nils Oncevay, died in an accident on March 23, 2007. The third, Edilberto Trucios died two months later on May 5, 2007.

Michael Huaranga, Saúl Quiroz and Antonio Ramos, workers for the San Sebastián outsourcing company, died of gas asphyxiation on February 8, 2009. They were working inside the Raura Mining Company mining unit in Lauricocha province in Huánuco region when they died.

The deaths of workers in the AESA outsourcing company due to poisoning are related to the fatal accident that occurred in February 2011. César Ccente Lulo and Juan Huaranca Santander died while working at the Acumulación Nelson X of the Barbastro mining company located in Huancavelica.

In May 2017, AESA worker Percy Carbajal Ramírez died from intoxication after being exposed to high levels of radiation inside the Carahuacra mine, a concession of the Volcan mining company in the province of Yauli in Junín region.

The contractor companies with the most workers killed by gas poisoning or asphyxia in the mines are Servicios Mineros La Esmeralda S.A.C., Operations Mineras San Sebastian EIRL. y Administración de Empresas S.A.C. (AESA) that register three deaths each one".

In the Uchucchacua mining camp in Oyón, workers report problems in the ventilation system of the shafts where they extract the minerals for the Buenaventura mine.

"Several of my fellow workers have been 'gassed' there because of the contamination formed when working in the mine and the lack of proper ventilation. We have been requesting improvements for years," said José Alcedo, secretary of the Union of Outsourced Workers of the Uchucchacua Mining Unit.

The workers of the Uchucchacua union call 'gassing' the inhalation of toxic gases inside the mine during drilling works. Photo: Milagros Salazar / Convoca.pe

The president of the Oyón peasant community, Héctor Miguel Facundo Damaso, told Convoca.pe that it is imperative that the workers' demands be met; it is essential to "offer all the conditions" to protect the lives of workers, many of whom are frequently are from the area or are relatives of community members.

Facundo Damaso recalled that in 2018, the community signed an agreement with Buenaventura, which ceded the company more than 500 hectares of land so that it could expand its operations and "enable a chimney to improve ventilation”.

The president of the peasant community of Oyón pointed out that Buenaventura must provide all security guarantees for its workers. Photo: Milagros Salazar / Convoca.pe

Through Apoyo Comunicaciones consulting firm, Buenaventura responded that the company has made "large investments in projects aimed at improving the mine’s main and auxiliary ventilation" and that in the Uchucchacua unit " there have been no fatal accidents related to ventilation problems in the past seven years”.

According to the Ministry of Energy and Mines database, the last accident due to ventilation problems occurred in June 2013, which caused the death of Teodoro Taipe Vásquez. He died at the age of 51, intoxicated by gas inhalation inside the mine.

At that time, his relatives lodged a complaint for the death and demanded compensation, which was unsuccessful. According to the documents consulted by Convoca.pe for this investigative report, the Mixed Provincial Prosecutor's Office of Oyón closed the case. Teodoro Taipe’s children continue their effort to demand economic reparation from the Contrata Minera Cristobal E.I.R.L. and Buenaventura, this in the midst of the recent death of their mother to COVID-19.

In Uchucchacua, rockfall is the most recurrent cause of death, which led to the death of four workers in fatal accidents in 2008, 2009, 2014 and 2017. Eber Apaza Ricra, the husband of Martha Zúñiga Palomino, the widow who supports her son Luis by selling food in Oyón's main market, was one of these deaths. In April 2020, Martha contracted COVID-19 and since then she feels that her health is no longer the same. She sobs, "There are a lot of us widows; we have been forgotten”.

When her husband died, Martha Zúñiga had to support her son Luis by selling fruits in the main market of Oyón. Photo: Milagros Salazar / Convoca.pe

In Uchucchacua, rockfall is the most recurrent cause of death, which caused the death of four workers in fatal accidents registered in 2008, 2009, 2014 and 2017".

Public Prosecutor’s Office Investigations Lead Nowhere

When a mining worker dies, the company in charge of operations is obligated to immediately inform the Peruvian National Police to start the process for the legally sanctioned removal of the body. After identifying the body, police officers notify the Public Prosecutor's Office so that it can begin investigations into the causes and the responsibilities for the death.

Police and prosecutorial sources in the mining areas of Huarochirí and Oyón provinces state that companies often do not immediately inform the police about these fatal accidents.

During prosecutors’ investigations, the responsibility usually falls on the backs of the supervisors who were on duty when the accident occurred. When evidence and witnesses are dependent on the company with the concession, a veil of silence covers the area.

The Casapalca police station has a patrol car for its work. In that same patrol car he has many times carried the corpse of one of the deceased workers in Alpayana S.A. Photo: Luis Enrique Pérez / Convoca.pe

Convoca.pe research found that nine out of ten prosecutors’ investigations for the 11 deaths of outsourced workers at the Uchucchacua mining unit in Buenaventura were closed. Of these ten cases, eight were closed between 2008 and 2019: three cases were closed in the Mixed Provincial Prosecutor's Office of Oyón and five others were shelved by the Judicial Branch.

The five closed cases by the Supranational Court of Preparatory Investigations of Oyón were shelved because officially it is known that the victims’ family members did not have sufficient proof to identify the defendants. Beyond having been closed without achieving convictions, all four cases coincided in indicting the supervisors, who are also workers, rather than the companies’ representatives.

The engineer Deyner Montoya, who was the mine manager in this production unit, was accused of manslaughter in the case of the collapse inside the Uchucchacua mine that led to the death of Zenobio Rojas Matos in August 2017. The accusation for the death of Zenobio, a worker outsourced by Resefer Mining, was shelved by the Judicial Branch in November 2019.

Workers from the Uchucchacua mine accompany the remains of Zenobio Eusebio Rojas Matos when he was transferred to the morgue. Video: Pasco Libre

The Public Prosecutor's Office indicted the former mine superintendent, engineer Freddy Espejo Zorrilla, for the alleged crime of manslaughter in the case of the accident that led to the death of Nemesio Espinoza Ramos in November 2008; Espejo was a worker in the Contrata Minera Cristobal. As mine superintendent, Espejo was responsible for enforcing occupational safety plans. The Judicial Branch shelved this case.

The information from the Public Prosecutor’s Office obtained by Convoca.pe revealed that one of the cases of the Uchucchacua mine also is stalled since February 2008, pending an appeal hearing in the Judicial Branch, presented by the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Huaura. This is the case of the death of Armando Cristóbal Cristóbal, who worked for the outsourcing company Proyecto Obras Mineras y Servicios. The accident occurred in May 2006; fourteen years have passed without obtaining justice.

Only one investigation on an accident in Uchucchacua continues in the preliminary investigation phase in the Mixed Provincial Prosecutor's Office of Oyón since October 2020; this is the case of Joohn Fausto Silva Mendoza who died in September 2016.

The Public Ministry opened 10 tax files on fatal accidents in Uchucchacua. Five were filed by the Judicial Branch and three by the Oyón Prosecutors. Photo: Headquarters of the Public Ministry of Oyón - Milagros Salazar / Convoca.pe

According to the information obtained by Convoca.pe, the Public Prosecutor’s Office opened investigations in 38 cases of the 45 deaths of outsourced workers who labored for the Uchucchacua mining units of Buenaventura, Volcan’s San Cristóbal mine and Alpayana S.A.’s Americana mine. These are the companies that concentrate the largest quantity of fatal accidents between 2006 and 2019.

Of these, 47.4% of these 38 cases ended as shelved in the investigation phase conducted by the Public Prosecutor’s Office and 13% in the Judicial Branch. Five of these cases continue under investigation and ten are in the judicial phase.

The Provincial Prosecutor’s Office in Yauli (Junín department), shelved seven of the eight investigations referred to accidents that occurred in Volcan’s San Cristóbal camp. One of these cases remains stalled in the Public Prosecutor’s Office: the case of Fredy Cuevas Ito, who died in October 2007 in a rockfall inside the mine. According to sources consulted, the legal opinion has been ready since November 2008 that could recommend the case’s final closure.

With regards to the workers who died inside the Americana mine unit of the Alpayana S.A. (formerly Casapalca S.A.), the Provincial Prosecutor’s Office of Huarochirí (Lima region), opened 20 investigations about these fatal accidents. Eight investigations were shelved in the prosecution stage; three are in the investigative phase and nine others have led to the formalization of the accusation in the Judicial Branch.

According to information from the Public Prosecutor’s Office, since August 2009, five investigations have been awaiting the opinion of the judges in the Huarochiri lower court. These are related to the death of the young man, César Herrera and his five workmates who in February of that same year died crushed while working in the Alpayana mining company. Eleven years have passed without sanctioning those responsible.

In the Huarochirí Corporate Provincial Prosecutor's Office, most of the investigations into fatal accidents in Alpayana S.A. have been archived. Photo: Luis Enrique Pérez / Convoca.pe

47.4% of these 38 cases of fatal accidents in the Uchucchacua, San Cristobal and Alpayana mining units ended up being filed in the investigation stage in the Public Ministry and 13% in the Judicial Power".

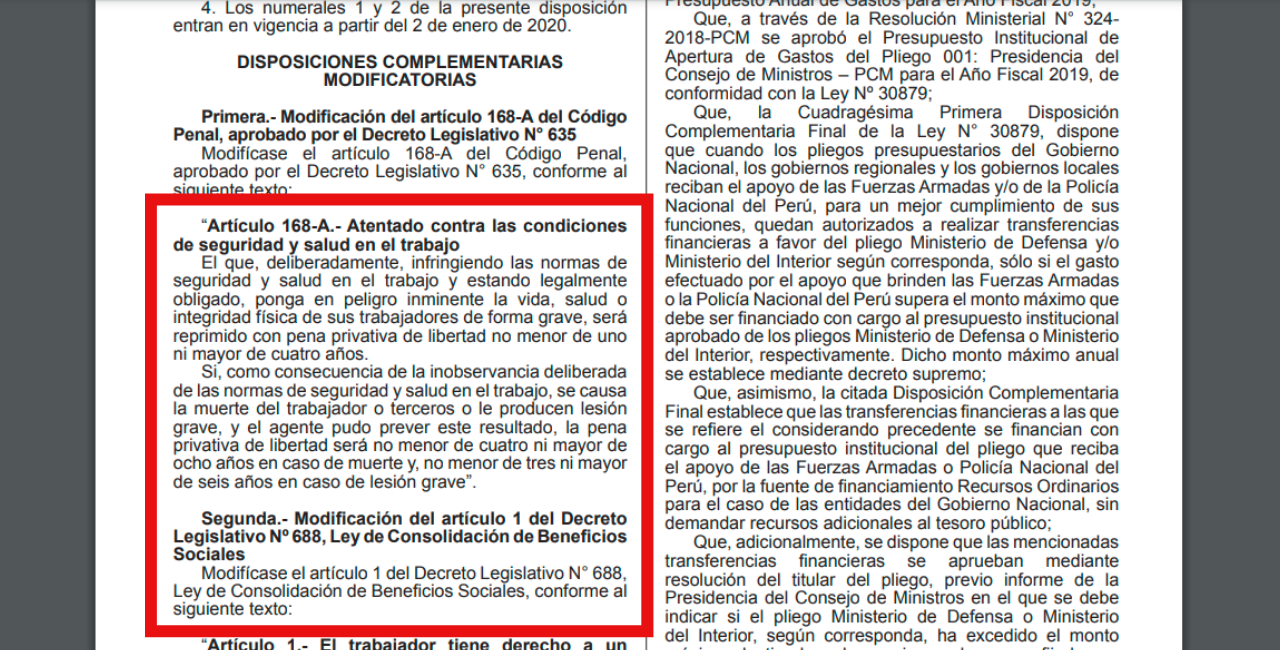

Why are prosecutors’ investigations being closed despite the records of hundreds of deaths due to accidents in mining camps? César Abanto Revilla, a labor lawyer and former state attorney in the Ministry of Labor, explains that there are a series of circumstances that make sanctioning the crime against occupational safety and health inapplicable, notwithstanding its inclusion in the Criminal Code.

This criminal offense was included in the Peruvian Criminal Code in August 2011; the government of Ollanta Humala determined that companies that do not take preventive measures to guarantee workers’ safety could be sanctioned with up to five years imprisonment. The code states that if this non-compliance leads to a fatal accident or serious injury to a company’s workers or third-party workers, holds a sentence of a minimum of five to a maximum of ten years imprisonment.

The original provision only lasted three years since the Humala administration modified the clause in the Peruvian Criminal Code through Law 30222. The law added that in order to impose the sanction, the company must have "deliberately" neglected to comply with the safety provisions or failed to abide by these regulations after having been notified by the Ministry of Labor. This same law allowed the State to offer debt forgiveness for mining companies with more than 4.7 million Peruvian soles (1.6 million US dollars) in fines for Sunafil-sanctioned labor violations, as Convoca.pe explored in a previous investigative report.

The criminal offense that defines the crime against occupational safety and health was again modified by the Executive Branch on December 30, 2019. This modification occurred after the death of two young workers who were electrocuted at a McDonalds restaurant in Pueblo Libre district in the city of Lima.

Peruvian Penal Code indicates that companies must "deliberately" breach safety regulations to be punished.

Since then, the National Superintendency of Labor Inspection (Sunafil) notification for non-compliance with safety measures is no longer necessary. This modification removed the exclusion of criminal liability that had benefitted the company when the worker dies or is seriously injured due to his/ her non-compliance with safety standards. Yet, this will only be applicable if the company engages in deliberate non-compliance of the established standards.

César Abanto affirms that the criminal offense which was added in 2011 was so broad and generic that it enabled the lodging of complaints in numerous circumstances. However, with the modification in 2014, the possibility of lodging a complaint was restricted and could only succeed if the employer knowingly violated occupational safety standards. For this reason, as Abanto explains, in the mining sector as in other economic activities, prosecutorial investigations of occupational accidents do not succeed and consequently are closed.

"The modification of the criminal offense established a series of conditions or circumstances that can hardly be demonstrated or produced. These adjustments have made it almost inapplicable", said Abanto. As a state attorney for the Ministry of Labor from January 2014 to September 2016 during the Nationalist Party government, Abanto was a close witness to these cases of impunity.

David versus Goliath

Legal cases that do not end in sanctions create despondency in the families of the workers who died in the mining camps. Once the legal procedures are exhausted, impunity prolongs the mourning.

The former Minister of Labor, Christian Sanchez, mentions that those who sue the companies for compensation face long processes that can be drawn out for three years or longer. With the judicial system’s inconsistent jurisprudence on labor issues, justice is not predictive and ends in rulings contrary to that sought by the victims’ families.

Faced with a tedious and prolonged case, most family members abstain from suing the companies and prefer to reach an out-of-court settlement in search of economic redress that will enable them to move forward with their lives.

Ynés Vergaray, a specialist in labor law, states that the mining company frequently proposes an extrajudicial settlement to the families. "Although family members obtain a smaller amount in conciliation processes, they avoid starting cases that can extend for years," she explained.

Julio Herrera played a central role in the tortuous judicial process for the death of his son César, who worked at the Alpayana mining company. The five families of the victims of the February 2009 collapse initially agreed to sue the mining company for manslaughter. However, after their hired lawyers changed positions, their initial willingness to file the case led to them giving up.

"You know how big companies are. I imagine that even the lawyers were pressured. At the beginning they were really ‘on-the-ball’ and then they began to be scared, saying that it couldn’t be done, and we had to leave it there," Julio Herrera told Convoca.pe. Herrera stated that their son’s life insurance policy, an estimated 90,000 Peruvian soles (31,250 US dollars), was paid out to the family.

Julio Herrera also indicated that the outsourcing company Corporación Minera Geminis S.A.C., for whom his son worked, offered jobs to the families in other mining units where the company provided services. "They told me that they could send me to work in Chimbote but thinking it over and seeing what happened to my son, I turned them down," he explained to Convoca.pe.

Gaps, Silences and Secrets of Oversight and Inspections

The inspection of occupational safety and health issues in large mining camps is typified for its gaps and secrecy.

The Ministry of Energy and Mines, the highest-level State entity in the sector, establishes the regulations for occupational safety in the mining industry. MINEM also grants the permissions for outsourcing companies to offer their services to the large and medium mining companies. In practice, MINEM functions as in-take desk.

In an email response to Convoca.pe, MINEM’s General Directorate of Mining stated that it does not have the authority to modify its official registry to remove companies in which workers were killed in mining accidents due to bad practices. This is the case despite MINEM having the authority over the registry.

The General Mining Directorate of the Ministry of Energy and Mines does not have detailed reports of the fatal accidents that occurred in the mining units. Photo: Andina

This MINEM directorate also conveyed that it does not register detailed reports of the circumstances of accidents. It can only issue sanctions against companies if they present false documentation, start or expand unauthorized activities, lack a safety engineer or impede the State’s supervisory functions.

Yet Osinergmin's Manager of Mining Supervision, engineer Rolando Ardiles, in an interview with Convoca.pe admitted that the supervisory body where he works and Sunafil do not work together. Osinergmin carries out programmed interventions in the mining units and conducts these immediately following a fatal accident, he assures.

"With Sunafil it is a bit difficult to coincide or engage in simultaneous supervision. I don't think that Sunafil will immediately conduct oversight actions when there is an occupational accident in the mining sector. This entity supervises a vast range of things and consequently it [mining supervision] is more complicated for them", contended Ardiles.

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Law, Sunafil is responsible for the compliance with the safety laws and regulations in the mining units, providing technical advice to the companies and workers on this issue; it must apply administrative sanctions for non-compliance with the regulations. The extent of compliance is unknown. Sunafil did not respond to the various requests by Convoca.pe for an interview. Convoca.pe was interested in obtaining information on the inspections in mining camps in light of the hundreds of deaths of the workers from outsourcing companies. The institution only presented some general figures.

In the email response to Convoca.pe, Sunafil stated that between 2014 and October 2020, its inspectors conducted 1,685 inspections in response to complaints about possible non-compliance with mining-related occupational safety and health regulations. Of these, 1,076 observations were related to outsourcing companies in the mining and quarrying sector. However, when asked about the names of these companies, this supervisory body kept silent.

Sunafil indicates that in the past six years it conducted 312 inspections in mining units in Lima; 120 in La Libertad; 112 in Pasco; 91 in Ica; and 88 in Junín. Yet, these figures greatly vary from the number of sanctions imposed by Sunafil on the outsourcing companies working for large mining companies.

Convoca.pe analyzed the database of the sanctioning processes that Sunafil initiated between April 2014 and July 2020. This study found 437 resolutions issued against outsourcing companies with the Ministry of Energy and Mines. Of these, 52 correspond to activities related to companies holding mining concessions, according to the documentation in the Application of Resolutions Issued by Sunafil’s Inspection System. Some of these mining outsourcing companies also have been sanctioned for infractions related to work in other sectors such as construction.

Sunafil's platform has not published the documents related to the 168 sanctions to outsourcing companies. In the 52 resolutions identified, Convoca.pe found that almost half of the cases, 23 are due to violations of safety and health standards by the outsourcing companies in the mining camps. Among these cases, four sanctioning processes were identified for accidents that caused the death of outsourced workers in Selín S.R.L., Corporación Minera del Centro S.A.C. (Cormicen), G&R Contratistas and Minera and Construcción y Transporte La Libertad S.R.L.

Rolando Ardiles, mining supervision manager: “With Sunafil it is a bit difficult to coincide or do a simultaneous supervision. I don't think that Sunafil will immediately supervise when there is a work accident in mining".

In October 2015, Sunafil imposed a fine of 202,125 Peruvian soles (62,771 US dollars) on Selín S.R.L. for not advising of the labor risks and for not supervising the safety of the work of Raúl Gutiérrez Tellería, who died on December 22, 2014. Raúl died when a pipe hit his body while he was installing the pumping system to extract water from the bottom of Southern Cooper Corporation's Acumulación Cuajone mine in Moquegua. Raúl, 38 years old, lost his life in one of the mines of Grupo Mexico, a transnational company that is the majority shareholder of Southern.

Cormicen S.A.C. was fined in November 2019 for the payment of more than 168,000 Peruvian soles (50,400 US dollars) for not complying with the effective supervision of the worker Dimas Tarazona Yanac, who died at the age of 49 in the San Juan de Arequipa unit of the mining company Century Mining Peru. Dimas died on June 7, 2018 from gas inhalation while drilling inside the mine.

The resolution with the sanction for the death of 58-year-old Ricardo Ramos Salazar specifies that the G & R outsourcing company did not provide suitable working conditions. The worker was not wearing a safety harness while doing maintenance work on the water pipes on the corrugated iron roof of the auditorium in the Orcopampa mining unit of the Buenaventura company. This negligence caused the worker to fall from a height of seven meters (23 feet) on September 15, 2017. Sunafil sanctioned G & R in July 2019 with 123,018 Peruvian soles (approximately 36,940 US dollars).

In September 2017, the Minera Construcción y Transporte La Libertad S.R.L. outsourcing company was sanctioned for not identifying the dangers and risks of the cleaning and installation of structures inside the mine. These are the actions that Naftuhim Solano Barra was doing on June 1, 2014 at the Retamas mine, a company with Peruvian capital. The 32-year-old worker did not survive the collapse that occurred. Sunafil imposed a fine of only 665 Peruvian soles (205.88 US dollars) on the outsourcing company that failed to comply with security measures.

Slide the image to view the resolutions

Mineral exploitation is a high-risk job that also requires specialized technical knowledge for its execution and inspection. Osinergmin is the state entity that supervises the mining camps’ compliance with safety measures to protect workers’ lives.

Between 2007 and October 2020, Osinergmin issued 1,886 resolutions that imposed sanctions against mining companies for non-compliance with safety regulations. As mentioned above, Volcan and Buenaventura lead the list with 161 and 138 sanction processes, respectively. The rankings also include the following mining companies: Ares, Los Quenuales, Nexa Resources Atacocha, Minera Poderosa, Southern Cooper Corporation and the Alpayana mining company (formerly Casapalca).

Osinergmin concluded that 120 outsourcing companies also were responsible for violations of the obligatory safety standards for mining companies holding a concession. As a result, Osinergmin issued 173 "solidarity sanctions" on the outsourcing companies between 2007 and October 2020.

Administración de Empresas S.A.C. (AESA), of Grupo Breca, leads the list of offending outsourcing companies. Osinergmin has initiated seven sanction processes initiated against AESA, which ranks as the company with the highest number of outsourced workers who died in labor accidents in mining camps. Three of these cases are linked to sanctions imposed on Nexa Resources for non-compliance with safety standards at the Atacocha mining unit in Cerro de Pasco department.

Convoca.pe asked Osinergmin to specify the safety regulations that the companies violated. However, the Management of Mining Supervision declared that it does not maintain this type of registry.

This investigative journalism portal requested all the sanction resolutions issued by Osinergmin Mining Supervision Management. The institution responded that these will be provided in February 2021.

Yet this is not the only information that is currently being held in reserve. In an interview with the Manager of Mining Supervision, engineer Rolando Ardiles, he indicated that there was a methodology to determine which mining units were most at risk. However, he stated that he is unable to make it public because "it is sensitive information" and any information that "filters out could affect the strength and economic solvency" of mining companies.

Ardiles added that the methodology allows them to establish a type of traffic light system in which the mining companies with high risks are identified in red, those with medium risks in green, those with low risks in blue and those with very low risks in light blue. In this way, Osinergmin can focus on its supervision responsibilities.

This public servant confirmed that his area identified that malfunctions in safety structure, which leads to landslides and rock falls, are the principal hazards in mining units. In the past fifteen years, 145 outsourced mine workers have died due to these, which is 33% of the total number of victims of occupational accidents.

The former Minister of Labor, Christian Sánchez, believes that if Osinergmin keeps information about the most unsafe mining camps secret, public authorities will be unable to make comprehensive decisions that would improve mine workers’ labor conditions. "A traffic light of risks should not just be used by a bureaucrat to do his monthly reports on the interventions conducted", he stated.

"What has Osinergmin done with this information? Did it share it with other entities in the occupational health system such as the Ministry of Labor and the Ministry of Health?" asked Sánchez. He affirmed that several entities are responsible for maintaining ineffective the safety system in the mining sector.

For this investigative report, Convoca.pe sent repeated emails to the communications areas of the Buenaventura, Alpayana and Glencore mining companies. It posed questions related to their responsibility in ensuring the safety of mine workers and the actions they took to offer redress to the families. Of these companies, only Buenaventura responded after one month of insistence. (See full answer)

Through Apoyo Comunicaciones, Buenaventura indicated that for occupational health and safety, it makes no distinction between personnel directly hired by the company and personnel hired by outsourcing companies. Of the total number of mine workers killed at its facilities, 3 were workers with a direct contract to the company and 40 were outsourced workers.

Buenaventura affirmed that in the past three years the mining company has been implementing a process of switching to outsourcing companies with a higher level of "operational and safety compliance", although it did not provide the names of these companies.

AESA, an outsourcing company of the Grupo Breca, preferred to stay silent and not provide answers regarding the mining accidents that led to the deaths of 11 of its workers, its safety standards, and the compensation for the families of the deceased workers.

"We have been forgotten. They just tell us that he died, left it there and it was over. That's the saddest thing," says Martha Zuñiga Palomino, the wife of Eber Apaza Ricra, who perished among the chute rocks in the Uchucchacua mine, located at more than 3,000 meters above sea level in Oyón. Martha, who chose to resign herself to raising her children alone insists "We can't beat the company”.

Main illustration: Manuel Gómez Burns

Menú

Menú

Buscar

Buscar

Sé el primero en leer nuestras publicaciones

Sé el primero en leer nuestras publicaciones