Santa Rosillo: an Amazonian community fighting illegal logging and the state neglect

Logging mafias have caused massive deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon. In just one year, 17,500 hectares of primary forest were lost in the San Martin region, a department bordering the Amazon, home to Quechua communities. Convoca.pe and CONNECTAS reviewed official information on authorized timber movements and seizures in the area, which evidences the lack of controls to detect illicit merchandise. The indigenous peoples of San Martin are fighting to stop this illegal logging, despite death threats and attempts against their integrity.

This story was originally published in Spanish on Convoca.pe and Connectas on January 11, 2023. Now is republished by the Human Journalism Network.

By Hugo Anteparra

Edition: Gonzalo Torrico (Convoca) and Connectas

Translation: Human Journalism Network

April 25, 2023

Quechua brothers Quinto and Manuel Inuma Alvarado and a group of indigenous ronderos came across a massive fallen log in the forest of the Santa Rosillo de Yanayacu community, San Martin, in the northern Peruvian Amazon. The tree was more than 200 years old, 40 meters long and with the thickness of eight bodies together. It has been cut down by illegal loggers in an area the villagers call Puca Quebrada. A few days before, the same indigenous patrol had seized another 18.8 m3 of the same species, illegally falling within the 23 thousand hectares in their territory.

“This tree is the only one that remains because the loggers have already stolen the rest,” explains Quinto Inuma, the community’s apu (Quechua for “guardian spirit”), visibly angry. According to this Quechua leader, the complaints have already been filed with the Environmental Prosecutor’s Office, the Regional Environmental Authority of San Martin and the Ecological Police. But this has not been of much help. The fallen trees appear regularly, although the authorities have already verified the depredated area and filed reports.

The Santa Rosillo patrol found this tornillo in October 2022. Photo: Hugo Anteparra.

In the last 20 years (2002-2021) the San Martin region has lost more than 394,000 hectares of primary rainforest, according to data from Global Forest Watch. While the peak of deforestation was recorded in 2012, with 37.9 thousand hectares razed, since then annual losses have ranged between 14 thousand and 21 thousand hectares. The figure for 2021 is 17,500 hectares. According to the Peruvian Society of Environmental Law (SPDA), illegal logging generates an economic loss for Peru surpassing USD 200 million per year.

Illegal depredation is continuous but also planned. This is demonstrated by photographs taken in the jungle by this media. In the forest of Santa Rosillo, trees can be seen with red paint marks: it is the announcement of their upcoming felling. Some drawings represent the shape of threatening guns.

“During the patrolling we do, we found two red letters, V and H, next to the drawing of a pistol on the stem of a tree. It is a message to avoid entering a deforested area. That means that they could attack us. But we are not afraid and we will continue to guard our forest to protect our future generations,” says Quinto Inuma.

The ronderos often find trees marked with drawings of firearms. They claim that these are warnings from illegal loggers. Photo: Hugo Anteparra.

How much legal and illegal logging is going on in San Martin today? The number is uncertain. But there are some indications that can be found in the official figures. One concrete fact is that, in the region, at least since 2019, there is a correlation between the aforementioned annual losses of primary forests and the authorizations to transport timber shipments.

After making various requests for information, Convoca.pe and CONNECTAS accessed data from the forestry transport guides issued by the Regional Government of San Martin between January 2019 and July 2022. These documents are used to mobilize wood shipments, from authorized extraction areas in the forests to markets, and certify their supposed legal origin. In 2019, shipments of 7,334 m3 were registered from San Martin’s forests. But in 2020, the year of the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the largest amount of timber shipments was recorded, despite two whole months of mandatory social immobility. That year 30,588 m3 of this forest material were accounted for.

In 2021 the number was 29,730 m3 and in 2022, only between January and July, the authorized figure reached 14,614 m3.

The most commonly extracted species from the forests of the entire San Martin region, year after year, is the Cedrelinga cateniformis, better known as tornillo. This is precisely the same wood that the Quechuas found felled in their territory. According to the same documents, the Regional Government of San Martin authorized the transfer of 28,291 m3 of this resource. The higuerilla (Micrandra spruceana), with 14,30 m3 extracted in the same period, is the next most exploited species.

However, the information contained in the transport guides is often falsified, and the logs of protected species travel, bypassing various authority controls along the way.

Patrolling the forest

While officials, legislators, police officers and inspectors are failing in their mission to protect the Amazon, the community members of Santa Rosillo de Yanayacu take on this function in the midst of threats and attempts on their lives.

To patrol in this place where government representatives rarely arrive, the Inuma brothers and the group of ronderos from the native community of Santa Rosillo wear uniforms with military colors. Those who do arrive frequently are the mestizos. This is what the natives call the migrants who, without sharing the same ancestral past or the culture of the Quechua, have settled in their territories to farm and are already beginning to impose their rules. The community members say that they are the ones logging and allowing other illegal foreign loggers to enter the forest, especially from Loreto, who are looking for new areas to continue extracting forest resources.

The community of Santa Rosillo de Yanayacu has seen deforestation increase with the arrival of the mestizos who are dedicated to taking over forest plots for cultivation. A report from the Regional Government of San Martin determines that between January 2020 and January 2021 alone, deforestation in the community’s forests amounted to 139.19 hectares, attributed to the start of agricultural activities. According to the Quechuas, a good part of these new farms on razed land are destined for illicit coca cultivation.

“Excessive deforestation was shown, since according to the analysis in 2019 there was a deforestation of 36.91 hectares and in 2020 of 73.84 hectares,” warns the official report. Likewise, the document points out that one can visualize the appearance of a clandestine runway in the forest, which has been built between October 2020 and August 2021. This is how drug traffickers enter the place.

The report from the Regional Government of San Martin.

For this report, we reached this area neglected by the authorities, besieged by both loggers and drug traffickers. In fact, we witnessed the violence that the Quechuas suffer on a daily basis.

On the morning of October 10, 2022, after several hours of patrolling, in the camp of the ronderos led by the Inuma Alvarado brothers, we heard the sound of several gunshots. After confirming that no one had been hurt, Quinto learned that it was another threat. The apu was soon warned by a phone call that they were being followed by about 25 mestizos, enraged after learning that the indigenous retinue was on its way to inspect an area undergoing depredation. The Quechua ronderos had to quickly pick up their patrol gear and begin their retreat for physical safety reasons.

Quinto Inuma asked his patrol to clear a path through the virgin forest to avoid being overtaken and avoid a dangerous confrontation. After an hour of physical labor, at a temperature of 35 degrees Celsius, the party was able to rest and stock up on water. Upon returning to Santa Rosillo, one of the mestizo farmers and a local resident insulted the Quechuas and warned them not to enter the deforested territories again. “The people should know why they are taking pictures in the plots. The territory belongs to all of us. You are not the owners. Let this be the last time you mess with us,” he said. The resident was identified as Manuel Pezo Villacrez.

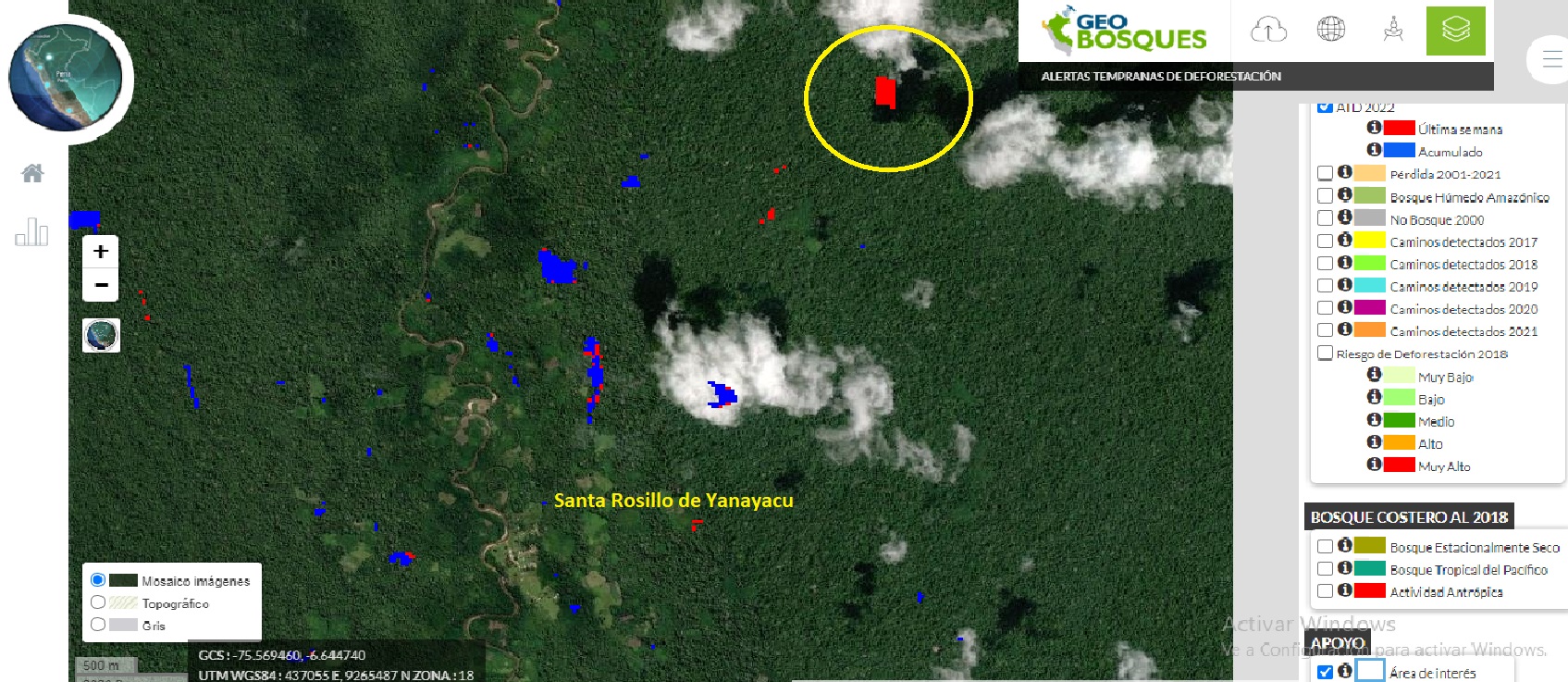

Days later, the satellite monitoring application Geobosques, of the Ministry of Environment, confirmed that 20 hectares of trees had been illegally cut in this area, between the last week of September and the first week of October 2022.

The satellite monitoring application Geobosques identified a loss of forest in the same patrolled area. Photo: Geobosques.

It wasn’t the first violent episode. Brothers Quinto and Manuel Inuma, as well as other members of Santa Rosillo, have previously suffered physical attacks and death threats, as recorded in the complaints they have filed with the Public Prosecutor’s Office. And even though the risks persist, the Quechua say they will continue to defend their territory.

“The jungle is our source of life and wealth,” says Manuel Inuma, former head of the community. “Trees are cut down almost every day. And, with that, the wild flora and fauna of the area we protect are becoming extinct. In the future, what are our children going to eat? That is why we are fighting against the deforesters,” he says.

Santa Rosillo’s ronderos seized 18.8 m3 of tornillo wood in October 2022. Photo: Hugo Anteparra.

Out of place

The logging business is so prosperous ―and the State so absent― that the logging mafias have begun to build their own infrastructure to facilitate the movement of illegal merchandise. This year, traffickers are using a dirt road in the Chipurana River valley that runs from San Jose de Yanayacu, in northeastern San Martin, to Tierra Blanca, in the Loreto region. According to locals, the road was built a few months ago by illegal loggers.

Satellite images from the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) confirm the short existence of this road, which, of course, does not exist on Peru’s road maps. In fact, when alerted by this media, engineer Gerardo Cáceres Bardález, manager of the Regional Environmental Authority of the Regional Government of San Martin during the 2018-2022 management, said he was unaware of said route.

“We do not authorize the construction of roads. In that area we have territorial boundary problems with Loreto and, if it exists, it was built illegally,” he said.

MAAP monitoring confirms the existence of the dirt road denounced by the inhabitants of the area. Image: MAAP.

What happens on the routes to be monitored? Timber transported through San Martin passes through up to six police stations and three forestry control posts. However, it is on the roads in this region where there is a clear lack of supervision. Often there is not enough presence of inspectors and regional officials to verify whether the species being transported in trucks match those reported on the forest transport guides.

For example, at the Corral Quemado checkpoint in the Amazonas region, which is located northwest of the San Martin region, this year alone the authorities intervened, in three different control operations, three trucks loaded with illegal forest species that had previously passed through San Martin. This demonstrates that in San Martin all of the control posts along the route of these cargo vehicles failed.

The facts demonstrate that the control of illegal timber in this region is more passive than active. We requested the report of interventions carried out by the regional government between 2017 and 2022. The information submitted only reported on operations carried out due to findings of “abandonment”, i.e. sawmills with merchandise left to their fate, not in activity. A total of 495 illegal shipments were found. The years with the highest number were 2019 (150) and 2020 (107).

Transport guides are not the only documents forged in this system of laundering illegal merchandise. In fact, corruption begins in the inventories of logging concessions and other extraction authorizations inside the Amazon forest. A legal and environmental think tank, Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), determined in 2019 that the inspections carried out by forest regents in these areas of legal extraction have served for some of these officials to approve false data on the quantities of forest resources available. The regents are officials appointed by the National Forestry and Wildlife Service (Serfor), an entity attached to the national government that is responsible for overseeing the sustainable use of these natural resources.

CIEL’s review of the Forest Management Plans, documents submitted by the concessionaires and endorsed by the regents, showed that in 2017 at least 13 regents out of 162 had signed documents that inflated the true number of trees available by up to 40%.

Fudging the number of trees in the Forest Management Plans then allows forestry transport guides to be used to ship greater quantities than the concession actually has. And that extra comes from somewhere else. This is how illegal timber also enters the legal system, mixed up in these shipments that are backed up with documents from a formal concession. When a police officer or an inspector requests these guides from the transporters, there is no way to corroborate at first glance that the information on the guides is false.

According to Mario Torres, who was head of planning in the Operations Office of the Regional Environmental Authority of the Regional Government of San Martin during 2022, and responsible for the issuance of the guides and inspections, the lack of budget does not allow them to carry out these operations on the routes. According to the official, between January and August 2022, his entity only received 100,000 soles (USD 26,300) to carry out operations against illegal logging in illegal sawmills and on highways. The money is not enough, he assures, as each intervention costs an average of 15 thousand soles (USD 3,900).

According to the Economic Transparency portal of the Ministry of Economy and Finance, since 2022 the Regional Government of San Martin has a budget line called “Forests with effective control and surveillance”. Despite having been allocated 1 million 686 thousand soles (USD 443,000 thousand) for 2022, the entity had only executed 24.3% of that amount as of last November 16. But they should have hurried because, at the end of the year, the execution reached 81.2 %.

We tried to communicate again with Mario Torres, who worked in the regional government until December 31, 2022, to find out how the public money was spent with such speed, but while he was in office he excused himself for not being able to answer our questions. With the beginning of 2023, which matches the change of political management in the regional government that occurs every four years, the new administration was also unable to provide explanations, as the officials consulted said that they still do not have access to the computer system.

Finding illegal timber on the banks of the Huallaga River in San Martin is a daily occurrence, according to locals.

José Anicama, an advisor to the senior management of the Forestry Resources Oversight Agency (Osinfor), a government oversight agency, says that while regional governments may have budgetary difficulties, there is also a problem with their management capacity. In recent years the budgets of these entities have increased considerably in general, but not those allocated to environmental struggles. “Although they have been given much more budget each year, there is a serious management problem that prevents that budget from being managed strategically and the regional government from directing the budgets that correspond to the area of forest resources and fauna,” he points out.

Indeed, while the total budget allocated in 2017 for the Regional Government of San Martin was 1,334 million soles (USD 351 million), this grew year by year to register 2,033 million soles in 2022 (USD 535 million). However, the budget item called “competitiveness and sustainable use of forest and wildlife resources” has had figures that have not followed the same progressive trend. In fact, by mid-November 2022, only 48% of the 6.9 million soles (USD 1.8 million) assigned had been executed. However, in only six weeks it experienced an unusual speed since on December 31 it had already almost doubled the spending reported in the first 11 months of the year and closed 2022 with 88% of execution.

The new officials of the regional government, who entered with the change of political administration on January 1st, explain that they will carry out an audit of all the contracts made by the previous administration. No wonder. The last regional governor Pedro Bogarín Vargas (2018-2022) was captured three weeks ago by the National Police, as he faces an investigation for integrating an alleged criminal organization and having committed alleged acts of corruption.

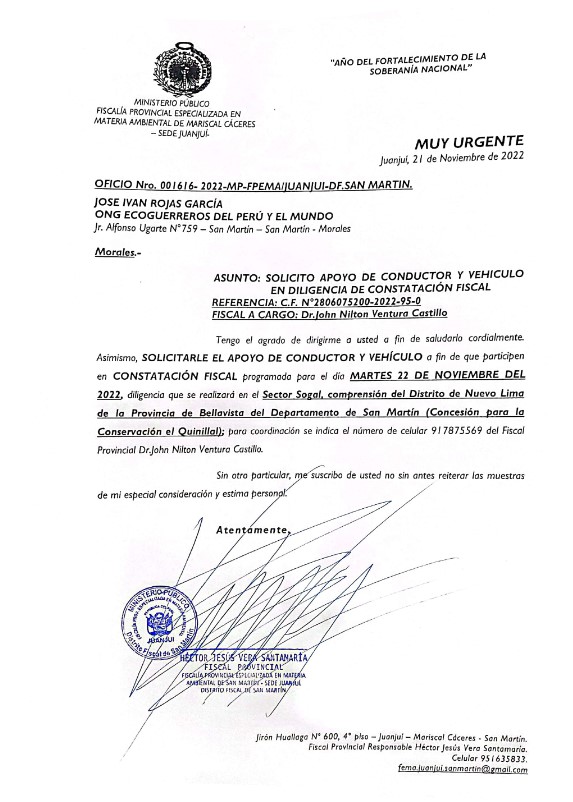

However, the lack of budget is not only evident in the Regional Government, but also in the poor logistics of the Specialized Environmental Prosecutor’s Office of San Martin. Convoca.pe and CONNECTAS had access to an official letter signed by the provincial prosecutor Héctor Jesús Vera Santa María on November 21, requesting the environmentalist and businessman Iván Rojas García for “support” to supply a driver and a vehicle to go to a fiscal verification in the province of Bellavista. The coordinations were in charge of the prosecutor Nilton Ventura Castillo.

This media spoke with Rojas, who assured that he had lent his vehicle on 23 other occasions, for free, throughout the year.

The prosecutor Héctor Vera Santamaría requests support on a “very urgent” basis from a private person.

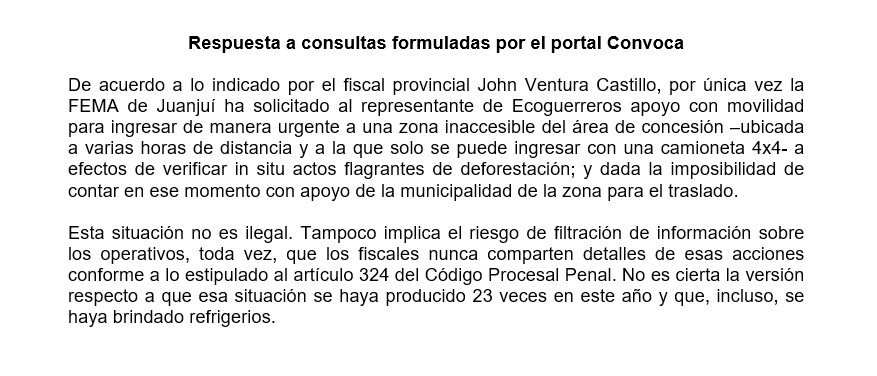

Why doesn’t the Prosecutor General’s Office use its own budget to pay for its operations? When consulted for this report, the Attorney General’s Office sent a brief written response about what happened. It did not comment on whether it lacked resources and followed the version of prosecutor Nilton Ventura. However, it pointed out that “this situation was not illegal” and that it was not true what Rojas said about the number of times he had been asked for this support. The Prosecutor’s Office assured that the one of November 21, 2022, had been the only request it had made, “given the impossibility of having support from the municipality of the area at that time.”

The Public Prosecutor’s Office sent a response through its communications office.

However, we were able to verify that Rojas has in his possession other letters that he claims were sent to him by the Prosecutor’s Office. The second most recent one is dated November 15, 2022, also with a “very urgent” character.

Constant danger

The indigenous leaders of Santa Rosillo are already acknowledged as recipients of the Intersectoral Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders of the Ministry of Justice, which has been operating since 2019. The system is focused on protecting the life and integrity of people whose risk situation has been verified by this entity, as is the case of Manuel and Quinto Inuma. The first was beaten and kidnapped in a dungeon in 2018. The second was also left badly wounded, with head and body injuries, in 2021. With their incorporation into the mechanism, they should have received guarantees to protect their integrity, but things have not changed significantly.

The community members complain that the lack of security in the area continues, despite the fact that their risk situation has been officially recognized. It is not uncommon for environmental defenders throughout the country to lack the promised guarantees, even though their lives are at risk. In 2022, the Ministry of Justice only allocated 40 thousand soles (USD 10,500) to execute this system, money that was quickly used up in consultancies. In other words, there is no adequate and realistic budget to ensure the integrity of the individuals expected to be protected.

“We already have seven families from the highlands who have taken possession to make their houses,” warns Quechua leader Quinto Inuma. The defender points out that those mainly responsible for these invasions are the municipal authorities, as they have not supported his request for the community’s lands to have a property title. “To overrule the community, they are putting in more migrants. But we are standing up to these invaders.”

Lawyer Cristina Gavancho León, the legal advisor to the native community of Santa Rosillo, assures that they have requested, on several occasions, that the National Police carry out inspections in the affected areas. However, according to her, the agents respond that they cannot go because it is a very dangerous area, where there is no security for them, because it is taken over by drug traffickers.

The centuries-old tornillo trees are highly sought after by illegal timber traffickers.

“If the police and the prosecutors don’t want to go, imagine the state of risk in which the apus find themselves, who fight with that every day,” says Gavancho.

Why are the guarantees for the leaders of Santa Rosillo delayed? We sought the version of Edgardo Rodríguez, director of the Human Rights Office of the Ministry of Justice, through the press office of that entity. At the close of this report, we did not receive a response to our request for an interview.

“Apparently they are not considering it,” says Gavancho, referring to enforcement of the protection protocol.

On the other hand, if the authorities continue to stand idly by, the damage will also continue to be registered in the ecosystems. “The absence of control and oversight policies, the presence of corrupt officials, and the scant promotion of economic alternatives allow illegal activities to be carried out on a daily basis, damaging the natural wealth and ecosystem services that the forests provide us,” says agronomist Marco Isminio, a specialist in natural resource exploitation in San Martin.

For example, in the constant community patrols carried out by the Quechua, they have discovered that the headwaters of the rivers and streams that supply water to the Pacaya Samiria National Reserve, one of the most biodiverse areas in the world, located in the neighboring region of Loreto, are in areas of San Martin that have been devastated.

“The headwaters of the watersheds, which originate in Cordillera Azul National Park, could dry up in the coming years and this will cause permanent damage to the Amazon. We hope that the authorities take this warning into account to prevent migrants from continuing to destroy our forests,” warns apu Quinto Inuma.

And this is not just an empirical assessment. Jaime Huamanchumo, an expert engineer in water resources, confirms that deforestation has a direct influence on the decrease of water in the rivers. “It is important to avoid it and start reforesting the areas that are deserted to generate conditions for more water,” he says. According to the specialist, a greater number of trees generates better rainfall conditions and water reserves.

Scenarios of devastation like this are recurrent in the headwaters of river basins. Photo: Hugo Anteparra.

In fact, one of the areas that is being most affected is the Chipurana River valley, where the new road has appeared, along which loggers are transporting their products. This watershed is the main source of water in this part of the Peruvian Amazon. Huamanchumo warns that, if measures are not taken, there will soon be water problems in the Pacaya Samiria National Reserve.

“The river used to be plentiful. You can see that now it dries up because of the wood that they depredate in the headwaters, the screws, our immense trees,” laments leader Manuel Inuma, who has seen how Santa Rosillo’s forest resources have been lost year after year.

“We want to leave a good memory for these children who are being born. If we don’t defend and the State doesn’t listen to us, then where are we going to stay?” says Manuel. “What are our children asking for? They want to eat, they want to drink, they want to dress. That is what we are fighting for. Our forest is the market, it’s the pharmacy, it’s our home. That’s what we live on and that’s where we live.”

Apu Quinto Inuma explains how trees are marked within the plots taken by migrants. Video: Hugo Anteparra.

Paper

The attacks come from different fronts, including the Congress of the Republic. A project to change the Forestry Law is being promoted in Parliament. If these proposals, which have already passed the first filter of the Agrarian Commission, are approved, the Ministry of Environment would no longer have jurisdiction in the process to establish forest zoning (areas where timber resources can be exploited, agriculture, etc.). The new zoning entity would be the Ministry of Agrarian Development. Different national and international institutions have warned that these modifications, which will allow the conversion of forests into agricultural zones, will increase the risk of deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon.

“We require that the environmental authority, which has a conservation focus, also has a say in that process,” says Cesar Ipenza, an expert in environmental law and public policy. “The Agrarian Commission continues to insist on saying ‘clean slate’ and removing the Ministry of Environment and having a role within zoning, but also in the definition of permanent production forests,” he warns.

The bill, which is being promoted by the political parties Perúi Libre, Alianza para el Progreso and Acción Popular, still has to be approved by the Andean and Indigenous Peoples Commission before being debated in the plenary of Congress.

Quinto Inuma does not believe in any of the authorities, including the regional ones. He says that the Regional Government has never approached the community, but that the documents presented and the complaints filed have been shelved. “The State is not helping us. It helps the illegal part more than the legality,” he laments.

Images: Hugo Anteparra.

Their lawyer, Cristina Gavancho León, notes that to date the Regional Environmental Authority of San Martin has not filed any administrative complaints against those who are indiscriminately logging Santa Rosillo’s forests. The Quechua are very concerned about this.

“Osinfor has never come, despite the fact that we keep providing our information by all means by making our physical, radio and internet reports, but nobody says anything. That is what bothers us. We have no help. We need them to help us title this territory of 23,000 hectares,” adds Quinto Inuma. A title deed to the forest would also allow the community to defend its land through legal means.

What about the police and the Attorney General’s Office? There have been three recent seizures of timber in the area, says the apu, but they have never notified the community as the victim in order for them to make a statement and continue with the complaints against the predators, who have so far gotten off scot-free. “That’s why [we say] they laugh at us because the authorities don’t work properly.”

Research: Hugo Anteparra. Editing: Gonzalo Torrico (Convoca) and CONNECTAS team.

This investigation was carried out by Convoca and CONNECTAS, within ARCO, with the support of the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), in the framework of the Initiative for Investigative Journalism in the Americas.

This story was originally published in Convoca (Peru), and is republished as part of the Human Journalism Network Programme, supported by the ICFJ, International Center for Journalists.

Menú

Menú

Buscar

Buscar

Sé el primero en leer nuestras publicaciones

Sé el primero en leer nuestras publicaciones