One January night in Kyiv, a company called Milton Group threw a glitzy New Year’s party for its staff. To the strains of a pop-rock cover band, contortionists and fire-dancers whirled under neon lights as young salespeople revelled in the spoils of a record-breaking year selling investments in cryptocurrencies and stocks. The firm’s management distributed cash, cars, and other prizes. One star salesman got a free apartment for a year.

But the real business of Milton Group was fraud. And even as its young employees partied in Kyiv, their victims across the world were losing their homes and assets.

“I have nothing to live for,” said one of them, a 67-year-old Swedish woman who is now homeless and destitute. She asked to remain anonymous because she was so ashamed of her situation.

The elderly Swedish woman who lost everything to Milton Group. Credit: Alexander Mahmoud/DN

Drummers at Milton Group’s New Year’s party. Credit: Lyubo-Dorogo

The people who scammed her also took careful steps to guarantee their anonymity. They hid behind stage names and conjured up entire fake cryptocurrency brands out of thin air, all to obscure the fact that their victims’ millions of dollars in “investments” were disappearing.

But this might be about to change.

Last year, a whistleblower approached Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter with a remarkable story of massive fraud — and the evidence to prove it.

He said he had been employed since August at Milton Group’s Kyiv office, tucked away into the upper floors of a city mall, but had quickly become disturbed by what went on there.

Through relentless onslaughts of phone calls and emails, Milton’s army of young salespeople scammed people around the world who were vulnerable to their sales pitch, whether that was because they were elderly, infirm, naive — or simply optimistic.

Journalists spent months following up on the extensive evidence provided by this whistleblower: thousands of call logs, customer lists, documentation of money transfers, and strikingly callous internal notes on how to target prospective victims, then keep wringing cash out of them for months.

Law enforcement officials interviewed by OCCRP and its partners say these types of fraud networks are difficult to dismantle, because they do most of their work by phone and online, hopping virtually across borders and even oceans to track down their victims.

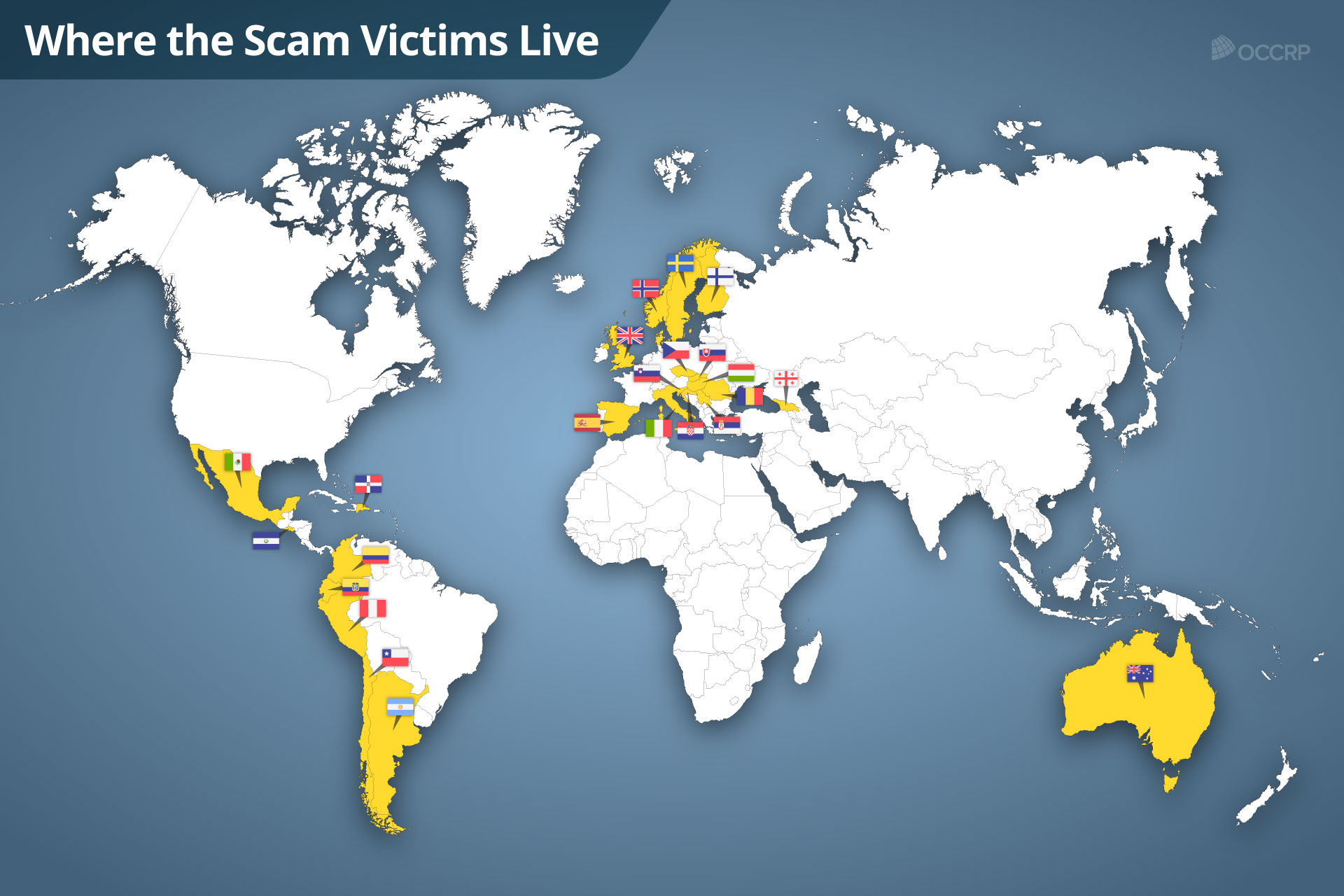

Because of this, we knew that any effort to tell this story would also have to be global. We helped to recruit journalists at more than 20 media outlets around the world to comb through documents, hunt down leads, and interview people who appeared on Milton’s client database.

Over several months, we pieced together the evidence to discover exactly how the scammers targeted their victims, and what happened to these people after they had lost everything.

The story took us from Kyiv to small towns around the world — to Georgia and Albania, where we learned of other call centers linked to Milton Group — and finally, to Sweden, where the whistleblower delivered his evidence to prosecutors last week.

Clutching a briefcase of documents, he said he was relieved to have the opportunity to do the right thing. His time inside the Kyiv fraud factory, the whistleblower told Dagens Nyheter, had been profoundly disturbing.

“I want justice to prevail,” he said. “It must be stopped.”

THE INVESTIGATION

Credit:OCCRP

INVESTIGATION BY:

- Dagens Nyheter: Axel Björklund, Mattias Carlsson

- OCCRP: Daniela Castro, Lindita Cela, Amra Džonlić (research), Sergiu Ipatii (fact-checking), Lawrence Marzouk, Julia Wallace

- Aristegui Noticias (Mexico): Juan Omar Fierro

- Convoca.pe (Peru): Carmen Alvarado

- Direkt36 (Hungary): Zsuzsanna Wirth, Gergo Saling

- El Confidencial (Spain): Marcos García Rey

- investigace.cz (Czech Republic): Pavla Holcová, Lukáš Nechvátal

- Investigatívne Centrum Jána Kuciaka (Slovakia): Daniel Antoni

- IRPI (Italy): Matteo Civillini, Lorenzo Bodrero, Lorenzo Bagnoli

- Helsingin Sanomat (Finland): Anssi Miettinen, Pauliina Siniauer, Elina Kervinen

- The Guardian Australia: Ben Butler

- The Guardian UK: Hilary Osborne

- KRIK (Serbia): Jelena Radivojević

- La Nacion (Argentina): Ivan Ruiz

- McClatchy/Miami Herald (USA): Kevin G. Hall and Shirsho Dasgupta

- Oštro (Slovenia, Croatia): Klara Škrinjar, Mašenjka Bačić, Matej Zwitter, Anuška Delić

- Plan V (Ecuador): Susana Moran

- Politiken (Denmark): Carl Emil Arnfred, Michael Olsen, Jonas Pröschold

- Revista Semana (Colombia): Sophia Gomez

- RISE Project (Romania): Attila Biro

- Siena.lt (Lithuania): Miglė Krancevičiūtė, Šarūnas Černiauskas

- Studio Monitori (Georgia): Nino Zuriashvili, Nino Ramishvili and Nino Tsverava

- Times of Israel: Simona Weinglass

- VG (Norway): Synnøve Åsebø, Sofie Amalie Fraser, Ola Haram

Menú

Menú

Buscar

Buscar

Sé el primero en leer nuestras publicaciones

Sé el primero en leer nuestras publicaciones